Avista Corporation

& the Spokane River and Spokane Falls

Avista Corporation

& the Spokane River and Spokane Falls

River of Kings

In years past, the Spokane River was home to millions of salmon, which brought bounty to the region's tribes

Jim Kershner

Spokesman Review, August 21, 1995

Everybody knows that salmon once surged through the Spokane River.

But not everyone knows that it was, literally, one of the king rivers of the Northwest:

The Spokane River spawned the biggest of the big salmon, summer chinooks (kings) that were commonly 50 to 80 pounds.

The Spokane River was one of the most productive salmon streams in the entire Columbia system.

The summer fishing camps at Spokane Falls were famous among many tribes, even tribes from far away. The total number of salmon running up the Spokane probably approached a million annually, of which about 300,000 were harvested by the Spokane tribe and other tribes.

(More)

“ Competing companies organized, purchased larger dynamos, and in the welter or competing claims to water, William S. Norman, F. Rockwood Moore, and others concluded that a single company to control the hydroelectric potential should be formed; they organized the Washington Water Power Company in 1889 to consolidate rights to river current and construct a power station using the high falls near Monroe. “

~ excerpt from John Fahey and Bob Dellwo, The Spokane River: Its Miles and Its History

Damming end to salmon runs

Lure of power at turn of 20th century led to multiple dams along Spokane River

Jim Kershner

Spokesman-Review, March 12, 2006

The Spokane River once ran free and wild – and then the Inland Northwest discovered the buzz of electricity. This electrical frenzy began in earnest in the 1890s, although the river was certainly a source of power before that. The first white settlers planted themselves in Spokane and Post Falls precisely because the river was ideal for driving sawmills and flour mills. Yet as early as 1885, an entrepreneur brought in a small electrical dynamo, attached it to a water wheel and strung up some downtown street lights. It soon became obvious that (1) electricity was the future and (2) harnessing it efficiently required blocking off the entire river, not just a channel.

So a consortium called Washington Water Power began buying up sections of the river for future dam construction. WWP's first projects included damming the Upper Falls in 1900 to provide power to the city, and then damming the river at Post Falls in 1906 to provide power to the Coeur d'Alene mines, according to the pamphlet "The Spokane River: Its Miles and History," by John Fahey and Bob Dellwo.

Yet these projects did not fundamentally alter one of the true natural glories of the Spokane River: Its enormous runs of chinook (king) salmon.

The Spokane River boasted an annual summer run of around a million chinook – and not just any chinook. This particular genetic strain produced some of the biggest fish in the Northwest. These hogs were commonly 50 pounds and sometimes 80 pounds. The Spokane River also had two steelhead runs and a small coho run.

None of those fish ever made it upstream of the crashing natural barrier of Spokane Falls. But the fish were everywhere in the 74 miles of river below the falls, including at the big Indian fishing camps at the mouths of Hangman Creek, the Little Spokane River and at Little Falls.

Ominously for the fish, however, several dam projects were in the works downstream. The first was the Nine Mile Falls Dam, about 16 miles downstream from Spokane, which was finished in 1908.

This dam was relatively low and apparently did not entirely block the fish runs.

Yet in 1909, The Spokesman-Review ran an article about a bigger project in the works: The Little Falls Dam, about 45 miles downstream from Spokane, right at the spot of one of most important Indian fishing sites.

The story boasted that the dam was larger than the Post Falls and Nine Mile Falls dams combined.

"The back water will reach over five miles upstream," said the paper. "The (turbine) units are the largest in the world, with the exception of one unit in Niagara Falls of the same size."

The project was finally finished in 1910 and had a predictably negative effect on the fish runs. The dam had only a rudimentary fish ladder and the evidence is unclear about whether it worked or not.

This became a moot point just five years later in 1915 when the WWP's next big project, the Long Lake Dam, was completed just five miles downstream from Little Falls. The Long Lake Dam was considered the "world's highest spillway dam" at the time. It also had no fish ladder at all. Nothing made it past Long Lake Dam.

The old newspaper stories about these dam projects are full of wonderful predictions about power and irrigation, yet I could find no mention of any public debate about salmon. Electricity was what mattered.

However, I did run across a later reminiscence from an old settler on the river, who called the day the river was blocked "a sad day for the pioneers who had grown to depend on the salmon." Then he added, "But for the Indians, it was a catastrophe."

The Spokane River salmon story came to a final end in 1939, when the Grand Coulee Dam was completed on the Columbia River. The dam had a huge economic impact on the region, providing both power and irrigation to previously arid lands.

Yet the Grand Coulee also blocked all salmon runs upstream, including the runs that remained in the lower 29 miles of the Spokane River. When the Grand Coulee had its grand opening, the last of the great Spokane River salmon runs were history.

Additional Resources

John Fahey and Bob Dellwo, The Spokane River: Its Miles and Its History (PDF)

John Osborn, MD, Restoring the Spokane River watershed: Looking back, Looking Forward (Powerpoint Lecture)

Avista’s Little Falls Dam, finished in 1910, was constructed on an important Indian fishing site, and extirpated the salmon runs on the Spokane River. Today, tribes are looking at how to restore the fishery.

(Photo: John Osborn)

The salmon came up to the river in full force up to the time . . . when the Washington Water Power Company built Little Falls Dam. . . When Little Falls Dam went in, it stopped the salmon from migrating up river when it was finished in 1911. The salmon carried on for quite a few years after that below the dam . . . until Grand Coulee went in and that was the end of it.

-- Alex Sherwood, former chairman of the Spokane Tribal Council, 1973, quoted in "Compilation of Information on Salmon and Steelhead Total Run Size, Catch and Hydropower Related Losses in the Upper Columbia River Basin, Above Grand Coulee Dam."

John Osborn photo

The Spokane River produced the biggest of the big chinook (king) salmon. This whopper was pulled from below Little Falls in 1938 by a Spokane Indian tribal member. (Spokesman-Review, photo courtesy of Alan Schultz)

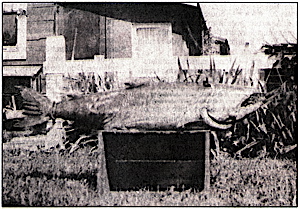

Monument to the first EuroAmerican settlement in the Spokane River watershed at Spokane House.

(Photo: John Osborn)

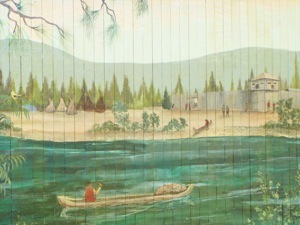

Mural from Spokane House Interpretive Center.

(Photo: John Osborn)

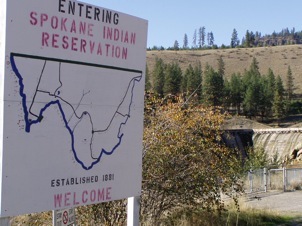

Spokane Indian Reservation, with Avista’s Little Falls Dam. Salmon are central to the lives of Indian nations in the Columbia River region.

(Photo: John Osborn)

Spokane River’s Little Falls, now dammed by Avista. Avista owns six dams on the Spokane River. With the exception of Little Falls Dam, Avista’s dams are operated under a federal license that will expire in 2007.

(Photo: GoogleEarth)

Spokane River, Avista’s Little Falls project.

(Photo: John Osborn)

Spokane Falls, 1881

Website Contents