Rep.

George Nethercutt: Listener?

By John Osborn,

M.D.

A nation that spent most of 1995 engrossed by

the O.J. Simpson murder trial and ignored Congress

using the budget process to grind up our

environmental laws is grumpily awakening to the

budget mess in the nation's Capital. One

Congressman in the cast of politicians is the

Speaker-slayer, Rep. George Nethercutt of

Spokane.

A year ago the "Gingrich revolution" was just

beginning. Tom Foley, congressman from eastern

Washington, was no longer Speaker of the House.

Eastern Washington voters replaced Tom Foley with

George Nethercutt, a publicly soft-spoken and

courteous campaigner.

Early in January, 1995, I traveled to

Washington, D.C., to meet with newly elected Rep.

Nethercutt, and to monitor the impact of the

Congressional budget process on forests. For the

past 10 years I have spent vacations on Capitol

Hill, prompted in part by the way in which

Congress's budget process is abused while setting

the nation's forest policies. A trail of stumps and

ruined streams leads from our clearcut forests to

hallways and backrooms of Congress. If you want to

know what government agencies really do, then

ignore their rhetoric. Look at their budgets.

Rep. Nethercutt welcomed me into his office in

the Longworth Building. We sat down: the television

was on one side of Nethercutt and I was on the

other. He looked at the TV as I spoke. Then looked

at me. Then back to the TV. I attempted to convey

the historic proportions of the transition underway

in the Columbia River region. Leadership is needed,

I said, to protect and restore our forests and

fisheries and to help rural communities through a

period of disruptive change. "Do you fish?" I

asked. No. "Hunt?" No. "Do you know anything about

the clearcutting and toxic metal pollution upstream

from Spokane?" No. Finally Nethercutt turned away

from the television and asked, insistently, "What

do you want from me?"

On March 1, I returned to Capitol Hill to

testify before the Senate Subcommittee on forest

policy, chaired by Sen. Larry Craig (R-ID). Over on

the House side of the Hill, the

Logging-without-Laws Rider was being shoved through

committees. Nethercutt supported this. The

Logging-without-laws rider was attached to a budget

bill like a bomb on a Christmas tree, and signed

into law by a flip-flopping President Clinton. Now

our public forests are falling to lawless

logging.

On June 1, another meeting with Rep. Nethercutt

was held, this time in Spokane. Nethercutt insisted

that "salvage" logging would not lose money,

disregarding conservative estimates that taxpayers

would lose hundreds of millions of dollars. He

attempted to defend his own rider on a budget bill,

so-called "Section 314", that would effectively

censor scientists, subvert public process, and gut

the Columbia River region's planning process.

Most of Nethercutt's constituents value the high

quality of life here: our forests, our world class

fishing, hunting, and lovely lakes. Nethercutt's

Sec. 314 and Logging-Without-Laws destroys the

Columbia River region's forests and fisheries. At

the same time, Nethercutt's actions will cost

taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars.

How to explain Nethercutt's decisions? Follow

the money. Money still gushes from timber

companies, and especially from the

Northern-Pacific-based corporations: Boise Cascade,

Potlatch, Plum Creek, and Weyerhaeuser. Money, the

mother's milk of politics, binds together the

corporate-government complex with the goal of

keeping a lock-hold on decisions about our public

forests and fisheries.

So let us return to George Nethercutt's question

from last January: "What do you want from me?"

First, stop intergenerational theft. Commit

yourself to sustaining our forests. As Republican

Gifford Pinchot recognized, preserving forests

through "wise use" can only occur with careful

planning. Careful planning requires using not

discarding the tools of sound science, economics,

and fair and open public process. Science-based

planning is the only way to avoid continued

malpractice that is destroying the Columbia River

forests and fisheries one of the most magnificent

river ecosystems in the world.

In short, George Nethercutt, provide the healing

leadership that we also asked repeatedly of your

predecessor, Tom Foley. You campaigned on being a

listener, not a speaker. Listen to more than the

Lords of Yesterday, George Nethercutt. Listen to

the land and to the people.

(1)

In extremis:

Columbia River

fisheries and forests

Rains devastate N.

Idaho forests and watersheds

Officials blame

clearcuts, roads in wrong places

for most of

damage

Jesse Tinsley/The Spokesman-Review

District Ranger Art Bourassa walks away from

a massive slide on Quartz Creek in the Clearwater

National Forest.

By Ken

Olsen, Staff

writer

The casualty list runs from Sandpoint to Lolo,

Mont., and the roster is far from complete.

Early estimates suggest triage will cost

taxpayers millions.

It's the worst damage to North Idaho's forests

most experts have ever seen: Roads overloaded with

water from recent storms fell off mountainsides,

walls of mud and debris tore up logged and unlogged

watersheds.

In Clearwater National Forest, federal officials

frankly admit the devastation was aggravated by too

many clearcuts and roads built in the wrong

places.

At least 28 roads are closed due to more than

100 slides, slumps and washouts. Some of the roads

probably won't reopen next summer, the U.S. Forest

Service said.

The Idaho Panhandle National Forests to the

north reports extensive damage to 200 miles of

roads in the Bonner's Ferry District alone. The

havoc raised by mudslides is worst in the St.

Maries and Avery Ranger Districtscutting off the

road between Avery and Wallace and blocking other

byways.

The forests appear to qualify for emergency

repair money

from the Federal Highway Administration.

"This is not a good picture," said Art Bourassa,

district ranger on the North Fork of the Clearwater

National Forest, as he pointed to a slide.

"I wish we didn't have a road up there," he

added, pointing to a new road in a recently logged

area 20 miles east of Dworshak Reservoir.

The rainstorms turned the road into an avalanche

that charged through a clearcut and took out a

piece of another logging road below it. The debris

tumbled into the North Fork of the Clearwater

River.

Not far away, raging Isabella Creek punched out

a 100-yard-long, 10-foot deep curve on an older

road, clear down to bedrock. It is the only road to

the popular Mallard-Larkins Pionpeer Area.

It definitely will be rebuilt, officials said,

starting with a rock barrier to shield the next

road from the creek.

Hardest hit was Quartz Creek Road, buried under

a massive slide 600 feet wide and 60 feet deep.

It blocks the easiest access to an active timber

sale.

But removal of the dirt and debris, and repair

of the road, will cost an estimated $1 million.

Many of the slides and washouts happened on

steep slopes with unstable soil. They involve roads

built four to 40 years ago.

This is a grand-slam education on how not to

manage forests today, officials said.

"Everything up to four to five years ago was

heavily clearcut," Bourassa said. "That probably

isn't sitting with what Mother Nature planned."

As for roads, "some shouldn't have been built,

based on location, drainage and stability," he

said.

In areas like Skull Creek and Quartz Creek,

"there were too many roads, too close

together."

That management won't be repeated, he said.

The Forest Service knew long before Bourassa

arrived here six years ago that several of those

roads were risky because the soil is so unstable.

"But if we didn't build in medium- to high-risk

areas, we wouldn't have a road down the North Fork

corridor," a major timber-hauling route, Bourassa

said.

Those risks are never figured into the cost of a

timber sale, but they are risks taxpayers will now

pay for, environmentalists said.

Former Forest Service employees contend the

current devastation is also partly a result of

logging the same watershed year after year, instead

of giving it time to heal.

Without those trees, there is nothing to drink

up rainwater and prevent erosion, said Al Espinosa,

who was chief fisheries biologist on the Clearwater

for 20 years.

For example, there are no roads above the Quartz

Creek slide.

Yet this watershed has sustained 200 million

board-feet of logging since 1965, much of it done

in the name of salvaging white pine.

In 1979, the most valuable white pine was taken

from the north slope by helicopter, leaving

primarily dead and dying trees on the slope that

slipped away last month.

It was salvage logging, advertised then as now

as essential to get the trees while they are still

valuable.

Spokesman Review December 8, 1995

Copyright 1995, The Spokesman Review Used

with permission of The Spokesman Review

Old forests east of

Cascades in jeopardy

·Scientists tell

Congress that old growth timber has been heavily

logged and isn't likely to survive another 100

years

By Kathie

Durbin of The

Oregonian staff

A century of logging has reduced old-growth

forests east of the Cascades to fragile islands too

small to support native wildlife, an independent

panel of scientists has concluded.

Six scientific panels briefed members of

Congress on their findings Thursday in Washington,

D.C. The scientists urged the U.S. Forest Service

to stop all logging of old-growth forests and

individual old trees in Eastern Oregon and Eastern

Washington immediately so the tattered forest

ecosystem can survive.

The scientists also said the agency should halt

all logging and road-building within broad

streamside areas and entire watersheds critical to

salmon. They said livestock grazing along streams

should end so that degraded rivers can heal.

The Clinton administration will heed the

recommendations as it begins writing a new

environmental impact statement for managing and

restoring the damaged eastside forests, said Mark

Gaede of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The outlook for survival of the eastside old

growth is grim even if the recommendations are

followed, said David Perry, a professor of forest

ecology at Oregon State University who served on

the seven-member panel.

"I personally think it has only a moderate or

low probability of surviving another 100 years

because of the threat of fires and insects," Perry

said. "This threat of natural catastrophe makes it

doubly important to protect all the remaining old

growth that we have."

The scientists recommended that two panels be

established to develop more detailed strategies for

restoring forest health and forest landscape.

The American Fisheries Society, the Wildlife

Society, the American Ornithologists' Union, the

Ecological Society of America, the Society for

Conservation Biology and the Sierra Biodiversity

Institute sponsored and prepared the report, which

was requested by seven House members in May

1992.

It was funded with $66,000 in grants from the W.

Alton Jones Foundation, the Bullitt Foundation and

the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Oregonian September 10, 1993

Brock Evans of the National Audubon Society said

the scientists' report proves that eastside forests

are in even worse shape than those west of the

Cascades.

"The watersheds containing these ancient forests

comprise most of the spawning and rearing habitat

for threatened and endangered Columbia and Snake

River salmon," Evans said.

But Chris West, vice president of the Northwest

Forestry Association, took issue with the idea that

the eastside forests can be saved by preserving

them.

"If we're going to improve and maintain forest

health in the eastside ecosystem, we're going to

have to manage the forest," West said. "Study after

study has shown that we can't just walk away."

The study includes the first-ever maps showing

the location and extent of eastside old-growth

forests, roadless areas and key watersheds. Steve

and Eric Beckwitt of the Sierra Biodiversity

Institute in North San Juan, Calif., drew on

mapping data and aerial photographs collected by 75

citizen mappers through the Audubon Society

Adopt-a-Forest project and used sophisticated

geographical information system software to prepare

the detailed maps.

The scientists found that three national

foreststhe Colville, Wallowa-Whitman and Winemahad

no old-growth patches larger than 5,000 acres. Of

seven old-growth patches larger than 5,000 acres in

the Malheur, Ochoco and Umatilla forests, only one

was protected.

Old-growth ponderosa pine, the most ecologically

and economically valuable tree species east of the

Cascades, is also the scarcest, they said. Just 3

percent to 5 percent of the original ponderosa pine

forest remains on the Deschutes National Forest, 5

percent to 8 percent on the Wihema and 2 percent to

8 percent on the Fremont.

"The geographical extent of old growth forest

ecosystems in eastside national forests has been

dramatically reduced during the 20th century," the

scientists said. "Continued logging of old growth

outside current reserves will jeopardize unknown

numbers of native species."

- EASTSIDE

FORESTS

- Here are the findings

of the Eastside Forests Scientific Society

Panel:

- · The extent of

eastside old-growth forests has been

dramatically reduced by logging since 1900.

0ld-growth ponderosa pine may cover only 15

percent of its original range in Eastern Oregon

and Eastern Washington.

- · Less than 25

percent of the old growth left on national

forests is protected.

- · At least 70

percent of the remaining eastside old growth is

in patches of less than 100 acres too small to

provide habitat for many old-growth

species.

- · Many areas

designated "old growth" in existing forest plans

aren't old growth at all.

- · Although large

roadless areas are important to such species as

bear, elk and wolverine, fewer than 8 percent of

roadless areas in the Blue Mountains are

protected.

- Recommendations

- · Halt all

logging of mature and old-growth forests to

create a "time out" until a protection strategy

is developed.

- · Cut no

individual trees older than 150 years or larger

than 20 inches in diameter at breast

height.

- · Do not log or

build new roads in areas where fish face

possible extinction or in watersheds that

provide the best remaining habitat and gene

pools for salmon and resident fish.

- · Do not build

new roads within roadless areas larger than

1,000 acres.

- · Establish wide

protected corridors along streams and wetlands,

including 300-foot wide buffers along yearround

streams.

- · Halt all

livestock grazing in riparian areas except under

strict protective controls.

The Oregonian

Forest Service officials frankly admit the

devastation in North Idaho was aggravated by

clearcuts and logging roads.

Landslide, Quartz Creek, Clearwater NF,

December 1995

Spokesman Review, Gerry Snyder photo

August 1, 1993 Copyright 1993, The Spokesman

Review Used with permission of The Spokesman

Review

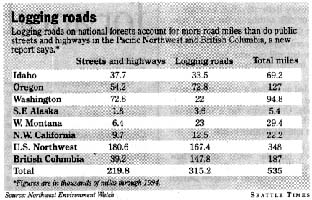

More miles of logging

roads than streams in NW forests

By Scott

Sonner Associated

Press

WASHINGTON

Logging-road mileage has more than doubled in

Northwest national forests since 1960, far

outstripping the pace of street and highway

construction in the region, a new report said

yesterday. WASHINGTON

Logging-road mileage has more than doubled in

Northwest national forests since 1960, far

outstripping the pace of street and highway

construction in the region, a new report said

yesterday.

More than 325,000 miles of logging roads now

crisscross public lands in British Columbia and

parts of six Northwest states enough to circle the

planet 13 times, according to a study by Northwest

Environment Watch, a Seattle-based non-profit

environmental-research center.

That's more than the 220,000 miles of public

streets and highways in the region, which grew

about 25 percent over the past 35 years.

Compared with highways, national-forest roads

have proliferated since 1960, more than tripling in

Oregon and more than doubling in Idaho and

Washington, the report said.

The study by John Ryan and Chandra Shah warns of

environmental damage caused by logging roads,

including erosion and sedimentation in streams that

harm dwindling salmon populations.

It urges a halt to logging-road construction in

the Northwest U.S. and zero growth in British

Columbia. It applauds Forest Service efforts to

remove roads as a central part of watershed

restoration in heavily logged national forests.

"Perhaps its most surprising finding is that

roads have surpassed streams as the most dominant

feature of the landscape in the region," said Alan

Durning, the center's executive director and former

researcher with Ryan at the Worldwatch Institute in

Washington, D.C.

"Today, outside of Alaska, more of the U.S.

Northwest is accessible to four-wheelers than to

salmon."

The report addresses the region's overall road

network public streets, highways and public logging

roads combined roughly 535,000 miles across British

Columbia, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, northwestern

California, western Montana and southeastern

Alaska.

British Columbia has the longest combined road

network, about 190,000 miles; followed by Oregon,

127,000; Washington, 95,000; Idaho, 69,000; western

Montana, 29,000; northwestern California, 22,000;

and southeastern Alaska, 5,000.

"Surprisingly, the Northwest's extensive network

of highways ... has expanded relatively little

since 1960," the report says.

"During this period, regional population nearly

doubled and the number of cars tripled, yet

recorded highway mileage increased only 25

percent."

That's partly because new housing developments

do not add much mileage compared with old rural

roads stretching across vast distances. Also, some

new suburbs simply pave over existing roads, the

report said.

National forests in the U.S. Northwest average

3.5 miles of road for each square mile of land, the

report said, citing 1994 figures by the Forest

Service.

Oregon's national-forest roads grew from about

20,000 miles in 1960 to 73,000 miles in 1994.

Washington's grew from about 9,000 miles to

22,000 miles, Idaho's from about 16,000 to about

33,000 and Alaska's from 251 to 3,600, the report

said.

Logging roads on British Columbia's public lands

now total about 150,000 miles.

Seattle Times December 12, 1995

(2)

Columbia River "Ecosystem

management"

Feds prepare to tackle

forest plan for East Side

By Jim

Lynch Staff

Writer

After crafting a plan for harvesting Western

woodlands, the Clinton administration is turning

its spotlight onto the Inland Northwest

forests.

The federal scrutiny arrives at the same time

environmental attorneys are shuttling arms to the

next old growth battlefieldthe timberlands of

eastern Washington and Oregon.

Clinton's top forester concedes the East Side

was largely ignored in the recent White House

forest plan, but said deciding how to best manage

the pest-plagued forests is now the top

priority.

"We're slowly marching our way eastward," said

Assistant Agriculture Secretary Jim Lyons in an

interview with The Spokesman-Review.

Lyons said the administration needs more

scientific information about East Side forests

before it decides how much timber can be logged

each year without jeopardizing the forests'

future.

It may take years before new management plans

are fully enacted, but some key information

surfaces later this month as reports on old growth

and forest health are completed.

Meanwhile, the East Side timber sale program is

in neutral with little more than salvage sales

offered on most of the region's public forests.

After devising a strategy for the eastern

Washington and Oregon forests, Lyons said the U.S.

Forest Service will shift to north and central

Idaho, the Inland Northwest's timber core.

The White House isn't waiting for a fractious

Northwest congressional delegation to resolve the

region's timber standoff that has pitted

environmentalists against both the Forest Service

and the timber barons.

"We don't need legislation to do what we want to

do over there," Lyons said. He described the

administration's goal as "attempting to protect

forest health in a manner that ensures sustainable

production of all resources, not just timber."

Lyons said West Side inventories revealed the

Forest Service overestimated the amount of timber

in its forests. He noted similar planning glitches

may have occurred in East Side forests.

The Forest Service continues to manage its lands

with plans devised in the late 1980s, but the

timber sale levels have slumped far lower than the

projected averages.

Most big sales have been delayed indefinitely in

response to a threat by the Natural Resources

Defense Council.

The San Francisco-based group filed a petition

against the Forest Service in late March seeking to

halt logging of old growth in East Side

forests.

"The East Side of the Cascades faces an

ecological crisis that rivals, if not exceeds the

one threatening the northern spotted owl," wrote

NRDC attorney Nathaniel Lawrence.

"Continued logging of the East Side's old growth

will inevitably lead to an environmental and

political train wreck."

The NRDC bills its petition as a way to protect

the American marten, pileated wnodpecker and

northern goshawk, animals not on the endangered

species list.

The threat of a lawsuit unnerves the agency's

Region 6 headquarters in Portland, which spent the

past few years in and out of court with

environmentalists over its old growth sales plans

in Western owl forests.

Tim Rogan, special assistant to Regional

Forester John Lowe, said the petition was one of

many signs the Forest Service needs to reevaluate

its East Side sales program.

"All these things are adding up," Rogan said.

"We decided we better put these sales that were

scheduled to go out on hold."

Rogan said the agency is gathering information

and doesn't know if future management strategies

will allow the forests to return to the sale

outputs deemed possible in the current plan.

"We have no idea what the (potential) timber

output of the area is," he said.

Richard Everett, a scientist team leader for the

Wenatchee Forestry Research Laboratory, is a lead

architect of a new East Side management

strategy.

Everett recently finished a five-volume report

on East Side forests which evaluates the condition

of timberlands and sets guidelines for ways to

better manage them.

Lyons called Everett's study a good start. "It

provides a generic blueprint," he said.

The study describes a management strategy that

steps back and views logging and other forest

activities from a ecosystem perspective.

With ecosystem management, foresters consider

how logging and other activities affect a large

region, such as an entire watershed.

It encourages managers to better mimic nature

with prescribed burnings, tree thinning and other

tactics.

Everett said it's far too early to predict how

the new system would affect timber sales. But he

said all sales will have to pass this test.

Panel Chairman Mark Henjum, a non-game

biologist, said the project has been difficult

because of conflicting information about old growth

stands.

Henjum said in some cases Forest Service old

growth maps were outdated and didn't reflect the

fact that some reputed old stands had already been

cut.

Lyons said the Clinton Administration focused

almost solely on the West Side in its forest plan

because it would have been too cumbersome to staff

a team of scientists with expertise on both sides

of the mountains.

"It doesn't mean we're not going to move

aggressively to put together a strategy on the East

Side," he said.

Lyons also said the decision to leave out the

East Side had nothing to do with House Speaker Tom

Foley. The speaker has expressed concerns that

Clinton's proposed forestry plan may jeopardize too

many timber jobs.

Lyons said after the administration gets a

handle on East Side forests, Idaho's federal

woodlands will receive similar scrutiny.

He said the management problems in Idaho are

different and in some ways more difficult,

complicated by the ongoing debates over roadless

areas and salmon.

"Does this activity improve the sustainability

of the ecosystem, or doesn't it?" he said, noting

sales must be redesigned if they don't pass.

"We anticipate that many sales will not pass

this screening process," Everett said.

He also estimated it could take at least three

years before ecosystem management will be fully

implemented throughout Washington, Oregon, Idaho

and Montana.

Fred Stormer, deputy director of the Pacific

Northwest Research Lab, said the new strategy

changes the way the Forest Service looks at its

land.

"We've been making product-based decisions

rather than ecosystem based decisions," he

said.

Andy Mason, assistant supervisor for the

Colville National Forest, said managers of the

northeastern Washington forest are not waiting for

an official directive to change their management

style.

"We're embarking on ecosystem management," Mason

said.

He said some proposed timber sales are now going

through the new "screen."

"Basically we're trying to figure out how we can

do ecosystem management and what it will mean,"

Mason said.

Other East Side studies that could help script

future timber plans include an old growth study by

the East Side Forest Scientific Society Panel.

Spokesman Review July 18, 1993 Copyright

1993, The Spokesman Review Used with

permission of The Spokesman Review

Project significant

undertaking for region

The Eastside Ecosystem Management Project is a

huge undertaking.

It will help determine, among other things, how

clean the region's water is, how much wood is

available from its national forests, and how many

different kinds of plants and animals survive into

the 21st century.

What's the main goal of the project?

To write a document, called an environmental

impact statement, that will guide management of 12

national forests and five Bureau of Land Management

districts in Eastern Washington and eastern

Oregon.

When will the environmental impact statement

be completed?

A draft version, which will list alternative

land management strategies, is due in February

1995. There will be a 90-day public comment period

before it is finalized.

Who will choose the "winning" management

strategy?

Two people: the Forest Service's regional

forester in Portland, and the Bureau of Land

Management's supervisor for Oregon and

Washington.

What's the next step in the process?

This spring the public will be asked to help

identify issues

that the environmental impact statement should

encompass.

Will the document's writers take jobs and

communities into consideration?

They stress that people are an important part of

the ecosystem. They will consider economic and

social values as well as ecological ones.

What's being done about federal lands in the

Interior Columbia River Basin that are outside of

eastern Oregon and Eastern Washington?

Federal officials plan to produce an

environmental impact statement for Idaho. There's

talk of writing one for Montana, too. Parts of

Idaho and Montana are already included in the

scientific assessment that's being done by the

Eastside project.

Will the scientific team conduct

research?

There is no time for that, although they may set

priorities for future studies. They'll be making

management recommendations based on existing

information.

Julie Titone Spokesman Review

March 9, 1994 Copyright 1994, The Spokesman

Review Used with permission of The Spokesman

Review

(3)

Congress censors science, guts public

process

Panel axes three fish

protection projects

By Roberta

Ulrich of The

Oregonian staff

In a move environmentalists denounced as a

"foolish idea," a House subcommittee this week

ordered an end to three sweeping forest and fish

protection projects east of the Cascades.

An industry spokesman said if the cutback

survives the congressional process, it probably

will be for the good.

But a spokesman for the National Marine

Fisheries Service, which is charged with protecting

endangered salmon, said the action "doesn't bode

well for habitat protection."

The subcommittee's action is only the first step

in the appropriations process. But it fits the

environmental and fiscal agendas of many of the

majority Republicans from the Northwest, giving it

a good chance of being enacted.

The House Appropriations subcommittee on

Interior Department agencies and the Forest Service

terminated three key fish protection programs:

Pacfish, Infish and the Interior Columbia River

basin ecoregion assessment. The report is not yet

public, but copies have been distributed to members

of the full Appropriations Committee.

Pacfish is a set of regulations that the

National Marine Fisheries Service developed for

streamside protection until the basin project

dealing with resident fish.

Much of the scientific study for the ecoregion

assessment has been completed, and draft reports

are planned for completion by Oct. 1, when the ban

on further project work would take effect. A draft

environmental assessment is not scheduled to be

finished until mid-winter, said Tom Quigley, the

science team leader for the multi-agency

project.

The agencies, including the Forest Service and

Bureau of Land Management, began the study in 1994

to adapt their forest plans to new demands,

including protection for endangered species of

salmon.

The subcommittee report notes that the ecoregion

project has garnered important scientific

information on forest health conditions.

However, the report added: "Despite this

accomplishment, the project has grown too large and

too costly to sustain in a time of fiscal

constraints."

The only thing salvaged for funding is

publication of the scientific information collected

so far.

Bob Doppelt of Oregon Rivers, an environmental

organization that has supported all three programs,

said the subcommittee report seemed to eliminate

analysis or alternative stream protection

proposals.

The report also ordered the forest management

agencies to amend their forest plans rather than

use the guidelines developed under Pacfish and

Infish.

Doppelt said the formal amendment process is so

lengthy "there will be no protection for a long

time, if ever" for salmon habitat in the eastside

forests.

Brian Gorman, a National Marine Fisheries

Service spokesman in Seattle, said removing the

Pacfish rules would "have a major impact on habitat

protection in the Northwest."

Jim Myron of Oregon Trout said sarcastically, "I

guess there is no threatened fish species." Then he

added, "It's like sticking your head in the

sand."

Bruce Lovelin of the Columbia River Alliance, a

coalition of industrial users of the Columbia and

its tributaries, said the subcommittee action was

"not too surprising." He said his group had not

looked at Pacfish as helpful and would welcome

changes in its rules for habitat protection.

Oregonian June 22, 1995

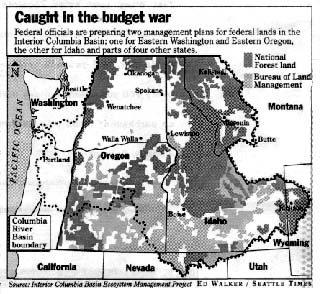

Forest effort pawn in

budget fight

By Eric

Pryne Seattle

Times staff reporter

The

budget war that now consumes Congress and President

Clinton is as big as the national debt and

Medicare. The

budget war that now consumes Congress and President

Clinton is as big as the national debt and

Medicare.

It's also as small as an office on Poplar Street

in Walla Walla.

Fifty scientists, planners and other federal

officials who work there have spent the past two

years assessing the present and plotting the future

of all federal forests and rangelands between the

Cascade crest and the Rockies.

Their charge: prepare a management plan for the

dry side of the mountains that is as

comprehensiveand perhaps as precedent-settingas

Clinton's controversial 19-month-old "Option 9"

forest plan for the west side of the Cascades.

Now their work may be cut short. The Walla Walla

project and the east-side forests have become pawns

in the budget war.

They are hardly a major focus of the debate in

Washington, D.C. But trees and salmon on 75 million

acres of national-forest and Bureau of Land

Management landan area almost twice the size of

Washington state may hang in the balance.

Northwest lawmakers, backed by timber and

agricultural interests, have inserted language in a

spending bill that would both narrow the project's

scope and bar the administration from imposing any

sweeping changes based on its findings.

The provision is one of dozens of environmental

"riders" that Congress has tacked onto the spending

and deficit-reduction bills now at impasse: Most

have more to do with policy than money.

That's hardly unprecedented. Budget bills must

pass each year to keep the government running. So

they become "Christmas trees," bills on which all

sorts of marginally related ornaments are hung.

A rider to a 1987 deficit-reduction bill, for

instance, took Hanford off the list of possible

sites for the nation's first nuclear-waste

dump.

What's different this year is that environmental

riders have become a major sticking point between

Clinton and Congress.

While the administration opposes the Walla

Walla rider, environmentalists worry the president

still could approve it if it's part of the right

package.

The Walla Walla project lacks the high national

profile of riders to change federal mining law or

open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil

drilling. While the Clinton administration opposes

the Walla Walla rider, environmentalists worry the

president still could approve it if it's part of

the right package.

When Clinton announced the outline of his

"Option 9" plan for west-side forests in 1993, he

rejected environmentalists' entreaties to include

forests in Eastern Washington and Eastern

Oregon.

Instead, he announced that a parallel planning

effort would be undertaken there. Officially it's

known as the Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem

Management Project.

A scientific team, based in Walla Walla, is

slated to complete an assessment of federal lands

between the Cascades and Rockies early next

year.

Other teams are piecing together management

plans based on that assessment. Drafts are expected

in February. One team, also in Walla Walla, is

focusing on Eastern Washington and Eastern Oregon.

The other, in Boise, is preparing a plan for Idaho

and parts of Montana, Wyoming, Nevada and Utah.

The issues are different east of the Cascades.

Fires are more frequent, for instance; scientists

say they do more damage today because past logging

and fire suppression have altered the

landscape.

Debate rages over logging's role in restoring

"forest health."

The east side also is home to the only Northwest

salmon already protected by the Endangered Species

Act. On federal lands, logging has been restricted

along Snake River tributaries where the fish

spawn.

Environmentalists have used lawsuits and the

threat of lawsuits to block timber sales. In the

1980s the national forests of Eastern Washington

and Eastern Oregon produced an average of 1 billion

board feet of timber annually.

Last year, timber sales there totaled just 380

million board feet.

The Walla Walla project aims to provide land

managers with a road map through all these

disputes. But timber interests fear it could

produce another Option 9.

That plan reduced logging in federal forests in

Western Washington, Western Oregon and northwestern

California to about one-fifth the level of the

1980s.

The Walla Walla project also is opposed by such

groups as the Washington State Farm Bureau and

Washington Cattlemen's Association, but for another

reason: fear that it could affect private

property.

Language inserted in the Interior appropriations

bill by Rep. George Nethercutt, R-Spokane; Sen.

Slade Gorton, R-Wash., and others would:

·Limit the scientific team's report to

"forest health" issues, excising information on the

condition of fish and wildlife.

·Bar the administration from adopting a

regionwide management plan, as it did in Option 9.

Instead, each national-forest supervisor would

decide what management changes are needed.

·Exempt timber sales from the Endangered

Species Act.

· Eliminate after December 1996 interim

policies that prohibit logging in relatively wide

streamside buffers.

The idea, says Nethercutt, is to get away from

"one

size-fits-all" regulation. "I think there's great

benefit to decentralizing these decisions," he

says.

Jim Geisinger, president of the Portland-based

Northwest Forestry Association, agrees. "We aren't

opposed to using new science and new concepts," he

says. "There may be places where 300-foot (stream)

buffers make sense. We just think there are other

places where they don't."

But Mike Anderson, a senior policy analyst with

the Wilderness Society, says the rider subverts

science and muzzles scientists.

"It's not wise policy to have everyone making up

their own mind in the Columbia Basin," he says,

"because you have salmon and other species that are

very wide-ranging."

Vice President Al Gore has labeled the Walla

Walla rider "a shortsighted action (that) would ...

guarantee more court battles and legal

gridlock."

But Anderson and Geisinger agree its fate in the

budget war probably hinges less on its merits than

other features of whatever legislation it's

ultimately packaged with.

"I don't think it's a make-or-break item, to be

honest with you," says Geisinger.

Seattle Times November 23, 1995

Nethercutt confuses

aquifer, ecosystem studies during WW

visit

Summary:

U.S. Rep. George Nethercutt criticized a federal

ecosystem study during a visit to Walla Walla last

week. However, some of his comments actually

referred to a different federal study. Summary:

U.S. Rep. George Nethercutt criticized a federal

ecosystem study during a visit to Walla Walla last

week. However, some of his comments actually

referred to a different federal study.

By Becky

Kramer 0f the

Union-Bulletin

U.S. Rep. George Nethercutt confused two federal

studies during a visit Friday to Walla Walla.

Washington's GOP congressional delegation has

been critical of a federal proposal to designate a

large area of the Palouse region as a "sole-source

aquifer"creating new regulations for groundwater

withdrawal.

Republican representatives sent a letter to

President Clinton questioning the sole-source

aquifer designation.

The letter did not address a study of Eastside

forests and rangeland, as Nethercutt had indicated

Friday.

Furthermore, a report sent to Nethercutt by the

state Department of Ecology also addressed the

sole-source aquifer designation. Contrary to

Nethercutt's remarks, the Department of Ecology has

not taken a stance on a study of Eastside forest

and rangeland ecosystems.

Department officials are still reviewing the

study, which is called the Interior Columbia Basin

Ecosystem Management Project, said ecology

spokeswoman Mary Getchell.

Nethercutt criticized the ecosystem management

project during several appearances Friday in Walla

Walla. He characterized it as a "huge grab for

federal control" that would lead to increased

regulation on private lands. He also referred to

the letter sent to Clinton and to the Department of

Ecology report, indicating that they addressed the

ecosystem management project.

George Nethercutt

"I don't know how the confusion occurred," said

Nethercutt spokesman Ken Lisaius. Nethercutt was

not available for comment Tuesday or this

morning.

Project leaders have been working with

Nethercutt's office to set a briefing with him on

ecosystem management.

"Our goal is to help folks understand what's

going on and set up good relations," said Patty

Burel, spokeswoman for the Interior Columbia Basin

Ecosystem Management Project.

The projecta joint Forest Service/Bureau of Land

Management effortis assessing the condition of

range and forest lands in Eastern Oregon, Eastern

Washington, Idaho and Western Montana. Project

leaders say they need to know the overall condition

of lands in that area to help them better manage

federal lands.

However, new management strategies developed in

the process will not extend onto private lands,

Burel said.

Walla Walla Union Bulletin February 22,

1995

House approves plan

that slashes funds for ecosystem

study

Summary:

A spending plan that cuts funding for completing a

study of forest health issues east of the Cascade

Mountains is headed for the U.S. Senate. The House

of Representatives approved it Tuesday. Summary:

A spending plan that cuts funding for completing a

study of forest health issues east of the Cascade

Mountains is headed for the U.S. Senate. The House

of Representatives approved it Tuesday.

By Union-Bulletin and

AP

WASHINGTON The U.S. House of Representatives

Tuesday approved a plan that guts funding for the

Walla Walla-based Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem

Study.

Spending for the so-called "Eastside study"

would be slashed to $600,000 in the 1996 fiscal

year, about a 90 percent cut from the $6.7 million

that had been requested.

The cuts were part of the overall Interior

Appropriations Act, which was approved on a largely

party-line vote of 244-181. One of the 14

Republicans who voted against the measure was

Oregon's 2nd District Rep. Wes Cooley, who

represents Umatilla County.

The cutback was proposed by Washington's 5th

District Rep. George Nethercutt. The reduced

funding, Nethercutt says, will allow project

officials to publish results of their 18-month

study and go home. The proposal does add $3 million

for watershed analysis.

Shutting down the process would affect two

environmental impact statementsintended to amend

dozens of federal forest plans and Bureau of Land

Management planning documents in the interior

Columbia Basin. The statements address issues that

range beyond individual forest boundaries such as

salmon, forest health and rangeland conditions.

Nethercutt says he's concerned about the cost of

the project and its magnitude.

The measure also directs the Forest Service to

remove existing guidelines for managing endan

gered salmon and trout stocks. Those strategies,

known as PACFISH and INFISH, had established

no-logging buffer zonessome as wide as a football

fieldaround key rivers and streams.

Environmentalists said today that the cuts to

the Interior Department and Forest Service would

harm public forests and fisheries across the

West.

"If the provisions of this bill are enacted, it

will be written across the Western landscape in

clear cuts, dead fish and red ink," said Jay Lee of

the Western Ancient Forest Campaign.

Nethercutt brushes aside the criticism: "I'm

sure that those supporting full funding are trying

to identify consequences," he said. "I tried to be

fair."

The bill also would impose 40 percent cuts in

the National Endowment for the Arts and the

National Endowment for the Humanities, a signal of

conservatives' strength. It also would force

reductions in the National Park Service, the Fish

and Wildlife Service, and the government's effort

to track endangered species.

But in a reversal, the House voted 271-153 to

continue the moratorium on low-priced government

sales of mining claims to federal land.

On a separate measure, the House Appropriations

Committee approved a $79 billion measure for

veterans, housing and other programs. However,

President Clinton said he would kill it unless it

is changed before it reaches his desk. The bill

would curtail efforts against air and water

pollution, halve aid for the homeless and dismantle

the president's national service program.

Walla Walla Union-Bulletin July 19, 1995

Lobbyists try to curry

favor with freshmen

By Jim Drinkard

Associated Press

WASHINGTON George Nethercutt, the Republican who

knocked off House Speaker Tom Foley, mingled in the

hallway of a Washington lobbying firm with about 40

lobbyists for mining, transportation, energy,

agriculture and high-tech interests.

Over coffee, the lobbyists made introductions

and small talk. Then they retired to the conference

room at Preston Gates Ellis & Rouvelas Meeds,

where partner Pamela Garvie introduced the incoming

freshman lawmaker and he made brief remarks

including one vital disclosure: his assignment to

the House Appropriations Committee.

Wednesday's reception at offices a block from

the White House was an example of how across the

city, lobbyists are reaching out to get acquainted

with new lawmakers, many of whom railed in their

campaigns against the stranglehold of special

interests.

Law firm partner Emanuel Rouvelas acknowledged

that lobbyists rank low in the public eye these

days. But the newcomers "tend to understand we are

not corrupt black-bag folks, not back slappers or

door openers. In effect, our job is to frame the

issues and advocate the issues in the best way we

can," he said.

A fairly common way to meet new lawmakers is

over drinks and hors d'oeuvres at a reception to

retire campaign debts. "There are fund-raising,

debt-retirement opportunities galore," said one

lobbyist who asked not to be quoted by name. "All

of them come in with debts," and remember those who

help them, he said.

"He is a very impressive guy," lobbyist Tim

Peckinpaugh said of Nethercutt. "He is the kind of

guy who is going to do well in this town."

Peckinpaugh, who arranged the sessiona

get-acquainted meeting, no fund raising involved is

one of several lobbyists at the firm with GOP

credentials. He emphasized that most of the

interests represented at the session are natural

constituents of Nethercutt, with important

operations in his district or in the Northwest.

Among them, for example, was Carl Schwensen, chief

lobbyist for the National Association of Wheat

Growers, a major commodity in Nethercutt's eastern

Washington district.

Preston Gates has planned nine such

get-togethers - mostly for new lawmakers from

Washington and Oregon, where its client base is

concentrated. The list includes

Microsoft and a host of maritime, timber, mining

and transportation interests.

"We are involved in a fairly substantial effort

to get to know and work with the incoming

members-elect," Peckinpaugh said. "This gives the

new members an immediate sense of who they will be

dealing with here in town, in terms of the key

interest groups."

In addition to hearing the new lawmakers' views

and priorities, it gives lobbyistsmost of whom have

worked on Capitol Hilla chance to offer practical

advice to the newcomers, he said.

"We think since we've been around a while and

have seen it from the inside, we can offer some

special insider tidbits on how you organize the

office to fit your particular district, where to

put district offices back home, that kind of

thing,'' Peckinpaugh said.

"The best way lobbyist types get to know new

members is through old members," said John

Rafaelli, a partner in a major law and lobbying

firm. "They introduce them to you, and you get to

be buddies."

For corporate lobbyists such as Raymond Garcia,

who represents defense and aerospace giant Rockwell

International, the first step is to call on newly

elected lawmakers whose districts include a

Rockwell plant.

"Most companies are going to be planning these

contacts, to just make people in Congress aware of

their interests," Garcia said. "Most new members

will be very interested in knowing who are the

economic entities in their districts. They want to

know as much as they can."

And it's terribly important, he added, to get to

know those freshmen going on the committees that

have power over each lobbyists' industry.

Lobbyist John Gordley, who represents soybean,

sunflower and canola interests, is focused on next

year's rewrite of the farm bill. If a new member

from an agricultural state needs help getting on

the Agriculture Committee, Gordley is

well-positioned: He used to work for new Senate

Majority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas, and is well

acquainted with incoming House Agriculture

Committee Chairman Pat Roberts, R-Kan.

The new lawmakers "like to have people come and

meet them," said Gordley.

Missoulian December 9, 1994

Oregonian July 20, 1995

Nethercutt still in

debt from '94 campaign

By David Royse

Correspondent

WASHINGTON More than halfway through his first

year in Congress, Rep. George Nethercutt still is

raising money to retire debt racked up during his

campaign last year when he unseated House Speaker

Tom Foley.

Reports filed with the Federal Election

Commission show most of the Spokane Republican's

contributors were individuals, although the

American Medical Association's political action

committee led a modest list of corporate and trade

association donors.

Nethercutt raised more than $142,000 in the

first half of this year, his FEC reports show.

Almost 70 percent of it went to a committee

dedicated to retiring the campaign debt, leaving

Nethercutt only $43,000 to spend on getting

re-elected.

So far, no one has stepped forward to challenge

the freshman congressman next year.

Nethercutt's 1994 campaign committee still owes

$34,700, including $9,700 of a $27,000 loan

Nethercutt himself made to his campaign.

Campaign watchers say more candidates than usual

ran up debts during last year's election races.

According to the citizens interest group Common

Cause, freshman lawmakers of both parties have

repaid more than $1 million in personal loans to

their campaigns. The largest debt among House

newcomers belonged to Ohio Republican Frank

Cremeans, whose 1994 campaign has repaid $174,000

in personal loans.

Alex Benes, an official with another watchdog

group, the Center for Public Integrity, said he is

not surprised by Nethercutt's

debt except maybe that it is not larger.

"Given that he beat the speaker of the House,

(Nethercutt's is) not a huge debt," said Benes.

This year's House freshman class raised

$133,186, on average, in the first part of this

year, putting Nethercutt in the middle among his

first-term colleagues in fund raising, according to

Common Cause.

The top freshman fund-raiser collected more than

three times what Nethercutt reported. Rep. John

Ensign, a Nevada Republican who also is retiring a

large debt from his 1994 race, had raised almost

half a million dollars through June 30.

Most of Nethercutt's contributions this yearboth

for last year's and next year's raceshave come from

individuals in Washington state. Political action

committees have given $42,500 to the 1994 campaign,

just less than half the total given to help retire

the debt.

However, Nethercutt's committee for next year's

race has received a far greater portion of its

money from individuals. Less than a fifth of the

re-election money has come from PACs.

The donations have come about equally from

fund-raisers and through mailed solicitations, said

Spokane attorney Lynn Watts, who has helped

organize fund-raising events for Nethercutt and is

a contributor herself.

Individuals who have given to Nethercutt range

from small-time contributors, who say they just

like his politics, to corporate executives, some of

whom already have given the maximum $2,000 each to

the campaign.

Spokane retiree Lola Jacobs is one of the

smaller contributors. Her February contribution of

$25 brought to $230 the amount she has contributed

to Nethercutt's campaign.

"I think he's honest," Jacobs said of

Nethercutt. "I knew his parents and they are very

good people, and I really don't like Tom Foley at

all."

Nearly half of the contributions to Nethercutt's

two committees have come from donors giving less

than $200.

But Nethercutt is not without large donors. His

biggest PAC contributor so far this year is the

American Medical Association, which gave him $5,000

to help pay off the 1994 debt.

By law, PACs can give no more than $10,000 to

each candidate $5,000 for the primary election and

$5,000 for the general election.

Jim Stacy, an AMA spokesman in Washington, D.C.,

said the organization does not publicly discuss its

contributions.

Corporate donors also include those with

interests in legislation considered by

appropriations subcommittees Nethercutt sits on, as

well as companies with local ties, such as Boeing,

which gave $2,000 toward helping retire last year's

debt.

Most major Spokane industries appear on

Nethercutt's funding report. Reynolds Metals and

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. each donated,

as did the Forest Industries PAC and Plum Creek

Management, a large timber concern.

International Paper PAC helped Nethercutt retire

his debt by $500, while Weyerhaeuser's PAC gave the

same amount toward the 1996 campaign.

Nethercutt's position on the appropriations

national security subcommittee may be what garnered

him contributions from some large defense

contractors. Naval shipbuilder Tennaco's PAC gave

him $1,000, while defense contractors Textron and

Allied Signal each weighed in with $500. General

Dynamics, another large defense company, gave

Nethercutt $500 toward next year's campaign.

Spokesman Review August 22, 1995

Copyright 1995, The Spokesman Review Used

with permission of The Spokesman Review

(4)

Columbia River ecosystem: What

future?

Committee sinks bid to

put watersheds, fish in ecosystem project

report

U.S. Senator Patty Murray, D-Wash., made a

failed attempt Tuesday to include the study of fish

populations and watersheds in the Columbia Basin

Ecosystem Management Project.

A House-Senate conference committee rejected the

amendment as the panel met for a second time to

make changes to the 1996 Interior Department

appropriations bill.

The committee made no changes to the project,

which examines new strategies for managing federal

lands east of the Cascade Mountains' crest. The

fiscal 1996 budget is estimated at $4 million, the

amount included in the appropriations bill, which

now is expected to go to the House and Senate later

in the week for final action.

President Clinton already has said he may veto

the Interior bill, listing omission of aquatics

issues from the Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management

Project as one of the problems.

Murray is frustrated that the committee didn't

want to consider it, Murray's press secretary, Rex

Carney, said today. U.S. Sen. Slade Gordon and Rep.

George Nethercutt, both R-Wash, were among the

conferees who voted against consideration of her

amendment, Carney said.

"It is incredibly shortsighted of these

members of Congress ... to ignore

science."

--Sen. Patty Murray D-Washington

"It is incredibly shortsighted of these members of

Congress to put their heads in the sand and ignore

science," Murray said in a press release. "My

amendment would have allowed the agencies to

approach their enormous task of resolving land

management conflicts in the Columbia Basin."

The bill contains language restricting the

project's scientific assessment to "landscape

dynamics and forest and rangeland health

conditions." Murray's amendment would have required

a "thorough analysis of aquatic ecosystems,

watersheds and fisheries populations."

Walla Walla Union-Bulletin November 1,

1995

Scientists balk at

restrictions on ecosystem data

SUMMARY: Scientists urge Clinton to veto

Interior Department spending bill if restrictions

on release of data in Interior Columbia Basin

Ecosystem Management Project aren't removed.

WASHINGTON (AP) Forty-five scientists accused

Congress today of trying to suppress research

warning of significant damage to fisheries, forests

and watersheds in the Columbia River basin.

The biologists, ecologists and other researchers

said a Republican-backed proposal in an Interior

Department spending bill would censor information

on the declining condition of the basin in Oregon,

Washington, Idaho and Montana.

President Clinton earlier promised to veto the

bill because of concerns about mining reforms. The

bill failed on the House floor last week and has

been returned to a House-Senate conference

committee.

The scientists, in a letter to Clinton organized

by the Pacific Rivers Council, said a section of

the bill would restrict data in an upcoming report

from the Scientific Integration Team as part of the

Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management

Project, located in Walla Walla. The team contains

scientists from the Forest Service, Fish and

Wildlife Service and Bureau of Land Management.

The section dictates that the report "shall not

contain any material other than" information on

forest and rangeland health.

Congress called for the project two years ago

and spent $15 million on the research to determine

the effects of logging, livestock grazing, water

diversions and other activities on dwindling fish

populations.

The scientists said the restricted report called

for in the spending bill would be "a

half-truth."

The bill "deliberately attempts to suppress

scientific information about public resources on

public lands important scientific information that

was generated at public expense," the scientists

wrote in urging Clinton to veto it.

The research includes updated conditions of

watersheds, trends of water resources and

population status of threatened, endangered and

sensitive species, including chinook salmon, bull

trout, westslope cutthroat trout, grizzly bears,

lynx and wolverines.

"The free flow of ideas and information is

critical if scientific knowledge obtained at

taxpayer expense is to contribute to sound decision

making," they said.

Walla Wall Union-Bulletin October 3,

1995

- President William Jefferson Clinton October

13, 1995

- The White House

- 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

- Washington, D.C. 20500

Dear Mr. President:

Our organizations have joined together to urge

you collectively to take a firm stand in

negotiations with Congress on the FY 1996 Interior

Appropriations Bill. We commend you on the strong

stand you have taken by threatening to veto this

bill in its current form, and we encourage you to

stand firm on your position not to compromise the

protection of America's natural resources. More

broadly, we urge you to forestall the enactment of

all riders that roll back environmental protection.

We further urge you to make the removal of Section

314 of the Interior Appropriations Bill and removal

of the language detrimental to the Tongass National

Forest non-negotiable items in your discussions

with Congress.

We represent a substantial part of the

sportfishing industry and many of the more than 50

million Americans who fish. The sportfishing

industry manufactures everything from rods and

reels to boats and motors and in 1991 accounted for

over 900,000 jobs and the production of goods and

services for many of our nation's anglers. Those

anglers in turn spent over $24 billion for direct

goods and services in that year.

Congress is currently finishing work on an

Interior Appropriations bill that we believe will

adversely affect sectors of the sportfishing

industry. The bill is harmful to our public lands

and could put jobs in jeopardy that would result in

economic hardship to communities that rely on

healthy sportfisheries. By reducing and eliminating

federal protections of our nation's western and

Alaskan fisheries this bill threatens resources

that are the basis of sportfishing communities'

livelihoods and of our sportfishing industry.

The Columbia River Basin's watersheds and

fisheries in Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon

are increasingly at risk as a result of relaxed

federal regulations and policies which should be in

place to protect them. Passage of this

appropriations bill, particularly Section 314,

coupled with the recent enactment of the rescission

bill imperils public lands fishing by making these

uses take a back seat to logging and grazing on

public land. In addition we think it shortsighted

to reject science-based ecosystem management and

limits to public participation as well as to

truncate long range planning as would occur under

Section 314.

In Alaska the bill would impose a four-year old,

discredited logging plan on the world class salmon

watersheds of the Tongass National Forest. It would

prevent citizen challenges of that logging, no

matter how harmful it proved to be to fish and

wildlife. By rejecting this provision you can avoid

making the same mistakes in the Tongass that have

been made in the Columbia River Basin. You can move

proactively to protect the Tongass and avoid losing

unique salmon stocks. The old logging plan mandated

by this legislation would put the Tongass on a

course parallel to that of the Columbia River Basin

a decade ago and set it at the same risk.

As negotiations with Congress continue we urge

you to insist that Section 314 is removed from the

bill as well as the directive to manage the Tongass

under the 1991 plan. Now is the time to stop

Congress from including authorizing language on

appropriations bills which repeals environmental

protections and is potentially harmful to the

industries, anglers and the communities that rely

on our nation's fisheries.

- Sincerely,

-

- Steven N. Moyer Paul Brouha

- Director of Governmental Affairs Executive

Director

- Trout Unlimited American Fisheries

Society

-

- Liz Hamilton Norville Prosser

- Executive Director Vice President

- Northwest Sportfishing Industry Institute

Association Sportfishing Association

-

- Paul W. Hansen Judy Guse-Noritake

- Executive Director National Policy

Director

- Izaak Walton League of America Pacific

Rivers Council

-

- Thomas J. Cassidy, Jr.

- General Counsel

- American Rivers

Flyfishing, St. Joe River in N. Idaho.

Don't kill lands

analysis, both sides say

Environmentalists,

timber officials tell Congress they need Columbia

Basin study

By Jonathan Brinckman The Idaho Statesman

Environmentalists and timber industry officials

have joined forces against a proposal to halt an

assessment of the health of forests and

rangelands.

The unusual agreement between two sides in the

heated war over Idaho's public lands stems from a

House Interior Committee vote last week.

The panel wants to virtually eliminate funding

for the final phase of the $31.6 million Interior

Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project. The

measure is to be considered by the full House next

Tuesday.

The project, launched in 1994, was to be the

foundation for logging, grazing and other

management decisions on 75 million acres of U.S.

Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management

property in seven Northwest states. That federal

land, in the eastern part of an enormous basin that

drains into the Columbia River, includes 31.4

million acres in Idaho.

"They're taking the first effort to do

large-scale ecosystem management and flushing it

down the toilet," said Rick Johnson executive

director of the Idaho Conservation League. Johnson

said he believes science-based timber management

would result in fewer clear-cuts.

Boise Cascade Corp. officials say a big-picture

analysis of public lands would enable the Forest

Service to free up timber sales now locked up by a

hodgepodge of interim environmental rules.

"As Boise Cascade sees it, the interim plans

have been very draconian. They've virtually shut

down the forests," said Doug Bartels, a company

spokesman. "We felt this would be the opportunity

for scientists to put their heads together, look at

the data and say, 'There, this is the right way to

manage this land.'"

The proposal to end the project would cut 1996

funding from $6.67 million to $600,000. It was

spearheaded by U.S. Rep. George Nethercutt,

R-Wash., a member of the House Interior

Appropriations Subcommittee. The subcommittee

called the project "too large and too costly to

sustain in a time of fiscal constraints."

The committee recommendation was lauded by U.S.

Rep. Helen Chenoweth, R-Idaho: "Eliminating this

project has been one of my top priorities since

coming to Congress. The federal government spent

millions of dollars and created no tangible product

and no jobs. All it attempted to create were more

regulations."

The House committee calls for all the data

collected during the past two years of study to be

assembled, peer-reviewed and made available to the

public.

A proposed last phase of the project, the

creation of an environmental impact statement that

would develop and assess alternatives for public

land management, would be scrapped.

The idea sounds fine to Brad Little, an Emmett

sheep rancher who chairs the public lands committee

of American Sheep Industry, a trade group. He

called the science valuable but disputed the need

for an environmental impact statement.

"The bottom line is, we don't need another

decisions document to complicate the life of guys

who are trying to administer the forestlands,"

Little said.

Mike Sullivan, a spokesman for Potlatch Corp.,

said that while he supports the study, he doesn't

worry that a final evaluation may not be done.

"We agree it makes sense to look at whole

landscapes when developing management plans," he

said. "That science will not be lost."

Steve Mealey, formerly supervisor of the Boise

National Forest and now manager of the eastern part

of the study, said ending the study - breaking

leases, transferring personnel, completing salary

obligations would consume virtually all of the

Forest Service's share of the proposed $600,000

allocation.

Little money would be left for publishing the

data, and project managers would be unable to make

management recommendations, he said.

"The science is documenting that we've got

seri

ous ecosystem problems, and the public is highly

divided about what to do about it," Mealey

said.

"The thing we could lose is the opportunity to

develop alternative ways to solve those

problems."

Idaho Statesman July 4, 1995

Editorial

Land study deserves

rescue

The U.S. House has foolishly proposed stopping a

study of forests and rangelands in the

Northwest.

Idaho's two senators need to team up with other

Northwest representatives to rescue this important

project from the slash pile.

The study will, for the first time, provide

agencies and the public a much-needed big-picture

look at how federal lands can best be managed. When

complete, the study will finally allow lands to be

managed as they shouldas complex ecosystems, not as

dozens of individual and unrelated parcels.

But, at the behest of Rep. George Nethercutt, a

freshman GOP congressman from Washington, the House

Interior Committee eliminated funding for the final

phase of the $31.6 million Interior Columbia Basin

Ecosystem Management Project. The House panel cut

1996 funding from $6.67 million to $600,000,

leaving enough to complete the scientific portion

of the study, but not the second half, the

environmental impact statement.

Killing the study now would be a mistake. The

scientific data needs to turned into usable,

on-the-ground policy.

The alternative is depressing and wasteful.

With

out new guiding principles, gridlock will continue

to reign as competing interest groups lock horns,

leaving the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land

Management immobilized in the middle.

Gridlock serves no onenot the loggers and

ranchers who make a living off public lands nor the

campers and hunters who recreate there. Yet

gridlock is virtually guaranteed unless the

Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management

Project is allowed to find solutions that avert

lawsuits and endless squabbles.

The project is designed to stop environmental

train wrecks before they occur. With proper land

management, groups wielding the Endangered Species

Act, for example, can be disarmed.

The project also can provide people who depend

on federal land for their livelihoods the certainty

they crave. When complete, the study can be a

useful guide for determining how timber and grazing

land can best be managed to sustain small

resource-based communities.

The study is a needed exercise that can lead to

more efficient use of public lands. It deserves

Congress' support.

Idaho Statesman July 13, 1995

Editorial

Ecosystem vote is

shortsighted

It's not often that the timber industry and

environmentalists join forces to fight

legislation.

But both groups are opposed to a House Interior

Committee recommendation to eliminate funding for

the final phase of the Columbia Basin Ecosystem

Management Project.

The project, launched last year, was to be the

foundation for logging, grazing and other resource

decisions on 75 million acres of federal property

in the eastern part of the basin, which includes

all federal land in Idaho.

Taxpayers have already funded a major portion of

the study, but some House Republicans want to kill

it with barely enough money left to publish the

results and make final recommendations, according

to Steve Mealey, former supervisor of the Boise

National Forest and a manager for the study. That

doesn't sound like wise use of tax dollars to

us.

Timber industry officials in Idaho support the

study because its recommendations could allow the

Forest Service to proceed with timber sales now

delayed because of temporary environmental

regulations put in place until an overall

management plan is completed. That's what this

study was supposed to do: make recommendations for

comprehensive plans that address management on a

ecosystem basis, rather than state by state.

Forests, watersheds, and plant and animal species

don't recognize state boundaries and often

management plans for adjoining states conflict.

Ironically, the committee vote to kill the

program came at the same time a report prepared for

the

Department of Interior revealed the nation's

natural resources are disappearing. Consider these

numbers:

· Ninety percent of the nation's old-growth

forests are lost.

· Ninety-five to 98 percent of virgin

forests in the lower 48 states had been destroyed

by 1990 while 99 percent of virgin deciduous

forests have been cut.

· Eighty-one percent of the nation's fish

communities have been harmed by human actions while