|

100

Years Later

|

|

|

|

Lewis

and Clark Fair Will Cost Five Million

Dollars and Will Be a Wonder

W.E.

Brindley

PORTLAND,

Ore. Feb. 3. - There are still four months

remaining before the Lewis and Clark exposition

will open its doors to the visiting thousands on

June 1 next and yet at this early date the grounds

have been put in shape, lawns sodded or seeded, and

eight exposition palaces, gleaming ivory white in

their ornamental staff, are completed. Some of them

are already being used for the storing of exhibits,

which have been arriving daily in carload lots

since the beginning of the exposition year. The

question as to the fair being completed in every

detail long before the opening day is settled

beyond the possibility of doubt.

So

great has been the demand for exhibit space that it

has been found necessary to erect another building,

and work on the structure has already been begun.

The new exhibits palace, which bears the name

Palace of Manufactures, Liberal Arts and Varied

Industries, is to contain 90,000 feet of floor

space, thus equaling in size the Agricultural

building, which is the largest structure on the

grounds.

The

exposition will commemorate the journey of

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William

Clark, who, with a party of hardy

adventurers, crossed the mountains in 1805

and explored the Oregon country, thus

giving the United States the power to make

her only acquisition of territory by right

of discovery.

The exposition, at first conceived by its

promoters as little more than a local

industrial fair, has now assumed

proportions that make it world wide in

scope.

|

The

readjustment made necessary by the construction of

the new building includes turning over the former

Liberal Arts building to exhibitors from Europe,

and giving over the entire space in the former

Foreign Exhibits building to oriental

exhibitors.

World

Wide in Its Scope.

The

exposition, at first conceived by its promoters as

little more than a local industrial fair, has now

assumed proportions that make it world wide in

scope. The addition of numerous new features from

time to time makes it certain that the fair will be

one that will prove of general interest. As in the

case of St. Louis, a specialty will be made of

"live" exhibits, making the fair an exponent of

modern manufacturing methods rather than a museum

of evidences of progress.

Foreign

participation will be on a scale not dreamed of

when the exposition project was conceived, almost

every nation on the globe being represented while

the majority of the states in the Union will make

official state participation, many erecting state

pavilions.

The

exposition will commemorate the journey of Captains

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who, with a

party of hardy adventurers, crossed the mountains

in 1805 and explored the Oregon country, thus

giving the United States the power to make her only

acquisition of territory by right of

discovery.

The

exposition will represent an expenditure

approximating $5,000,000. The site, by all odds the

most beautiful ever utilized for such a purpose,

occupies 402 acres and adjoins the principal

residential district of Portland. The site

comprises a natural park, and the principal

exhibition palaces, nestling among the trees,

overlook a beautiful little lake, called Guild's

lake, and the Willamette river. In the center of

the lake is a peninsula, which looks from the

mainland like a verdure covered island, while in

the distance rise four mighty snow capped mountains

- Mount Hood, Mountain Rainier, Mount Adams and

Mount St. Helens.

The

principal admission gates will be between pillars

of the ornate colonnade entrance, which is within a

stone's throw of Columbia court, the central plaza

of the exposition. The court consists of two wide

avenues, with beautiful sunken gardens between

them, and which are flanked by the agricultural

palace and the European exhibits building. On

either side of these buildings, with their short

sides facing the lake, are situated the other main

exhibition palaces, which bear the names, Oriental

Exhibits, Forestry, Manufacturers, Liberal Arts and

Varied Industries, Mines and Metallurgy, Fine Arts,

and Machinery, Electricity and Transportation. The

buildings, with the exception of the forestry

building, are all covered with ivory white staff,

and are built on one general architectural scheme,

embodying a free form of the Spanish renaissance. A

broad flight of steps, known as the

As

in the case of St. Louis, a specialty will

be made of "live" exhibits, making the

fair an exponent of modern manufacturing

methods rather than a museum of evidences

of progress.

|

"Grand

Stairway," lead from Columbia court to the

bandstand on the lake shore. The slope on either

side of the stairway is terraced, affording a

delightful resting place from which to listen to

the band concerts and watch the pyrotechnic

displays on the lake.

In

the western part of the site a considerable portion

of the grounds have been left almost in its natural

state, forming Centennial park, and beyond this

park, in a little valley, are situated the

experimental gardens, where all manner of western

farm and garden products will be displayed as they

actually grow.

On

the Trail.

Guild's

lake is spanned by the beautiful Bridge of Nations.

The end of the bridge adjoining the mainland will

be called the Trail. The Trail, which is to be the

amusement street of the fair, is 150 feet wide and

800 feet long. The shows will be located on either

side of a wide avenue. Many new attractions are

planned for this popular feature.

|

On

the Government Peninsula, which is reached by the

way of the Bridge of Nations, the main government

building occupies three acres. The structure is

flanked by two towers, each 260-feet high, and

ornate peristyles lead to smaller structures which

will house the territorial, irrigation and

fisheries exhibits, a fourth smaller building being

used as a life saving station. The government's

exhibit will represent an aggregate expenditure of

$800,000.

While

our own government will be the largest national

participant, nearly every nation that arises to the

dignity of a place on the map will be represented

at the exposition. England will maintain her

dignity against German, and Germany against France,

while Japan and Russia will struggle for supremacy

in

While

our own government will be the largest

national participant, nearly every nation

that arises to the dignity of a place on

the map will be represented at the

exposition.

|

a

battle of peace. China will have a great display,

and Siam and Ceylon, Spain, Mexico, Italy, Turkey,

Austria and Egypt will be represented. Even Morocco

and Persia will exhibit. Sweden and Denmark have

likewise fallen into line, as have Holland and

Belgium and numerous powers of less

importance.

Great

interest will center about the exhibits from Japan

and Russia, both nations having been attracted by

the oriental aspect of the fair. The Japanese will

occupy one third of the oriental building and are

planning for a big national pavilion, in which will

be shown their products, manufactures, educational

conditions, and displays of fine and liberal arts.

Russian participation will be on much the same

lines, particular attention being given to silk

weaving and other manufacturing

industries.

State

participation from every part of the Union

is now assured . The States Are

Coming.

|

State

participation from every part of the Union is now

assured and a number of the wealthier commonwealths

will erect pavilions which will serve as club

houses for their citizens visiting the fair. The

Oregon appropriation, $450,000, is the largest ever

made by a state of so small a population. The

Atlantic seaboard states have shown an interest in

the exposition that is a source of great

gratification to the management. It now seems

certain that New York's appropriation of $85,000

will be increased by $25,000. Massachusetts has

appropriated $15,000, and will move her St. Louis

building to Portland, while Vermont and New

Hampshire will erect pavilions. In the middle west,

North Dakota, Minnesota and Missouri will transfer

the cream of their St. Louis displays to Portland,

supplementing them with additional displays

gathered for the occasion, while Wisconsin,

Illinois, Michigan, and Indiana are likely to make

official participation of some sort.

The

main exhibition palaces bear the names

Oriental Exhibits, Forestry,

Manufacturers, Liberal Arts and Varied

Industries, Mines and Metallurgy, Fine

Arts, and Machinery, Electricity and

Transportation.

|

Of

the states of the Pacific Northwest, which are

directly interested in making the exposition a

success, Washington has appropriated $75,000 for

the erection of a building and the collection and

installation of a suitable display. California

originally appropriated $20,000, and this has

recently increased by appropriation to $90,000.

California will erect a building in the form of a

cross, each wing being a reproduction of an old

Catholic mission. Idaho has recently chosen a site

for a state building, which will cost about

$10,000, and will increase her appropriation to

cover the expense. Montana and Utah, which

originally appropriated $10,000 each, are expected

to make additional appropriations and erect

pavilions.

It

Will Be Unique.

The

Lewis and Clark fair will be unique among

international expositions in that it is built with

a view to compactness without crowding. The

exposition can be seen and studied within the time

and means which the average person has at his

disposal. The exposition will contain the cream of

earlier fairs, supplemented by valuable exhibits

collected especially for the fair.

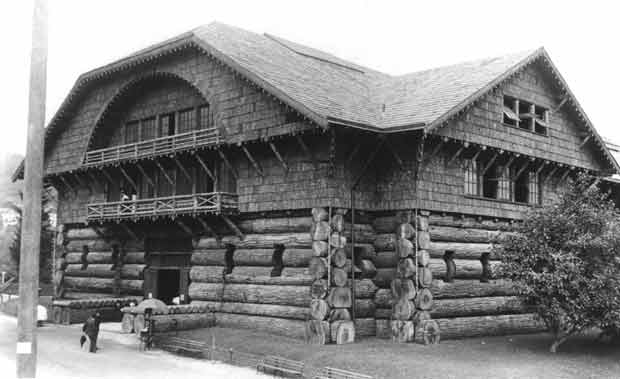

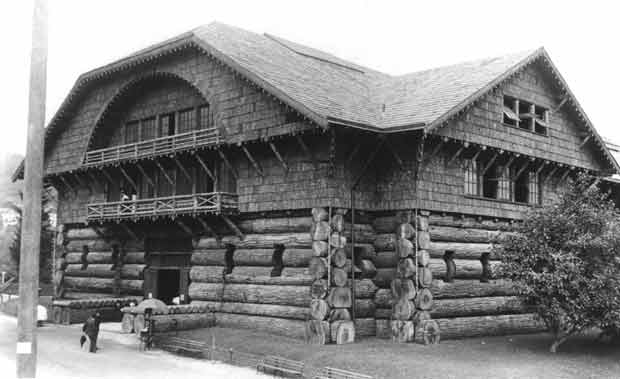

In

keeping with the intention of making the fair truly

representative of western life and western

resources, the forestry display will be one of the

most interesting exhibits at the fair. The forestry

building, constructed after the manner of a mammoth

log palace, is a structure unique in exposition

history. The building is 102 feet wide by 205 feet

long, and its great height is 70 feet. In the

construction of the building two miles of five and

six foot logs, five miles of poles and tons of

shakes and cedar bark shingles were

used.

Interest

Is Widespread.

The

exposition management has been showered with

requests for literature bearing on the fair, and

reports from the east indicate that a general

interest is being taken in the enterprise. The low

rates offered by the railroads, by which a person

living in the Mississippi valley can go and come

for $45, while people farther east may make the

trip at a one fare rate, assure a large attendance

from states east of the Rocky mountains. The

exposition authorities, while not wishing to seem

too sanguine, have no fears of small attendance,

nor of the fair not being completed in every detail

long before the opening day.

The

Spokesman Review, February 5, 1905, Copyright

1905. Reprinted with permission of The

Spokesman-Review.

For information on the Centennial

exposition:

www.ohs.org

(to "Collections", then "Manuscripts" for

references associated with Portland's 1905 Lewis

& Clark exhibition, or contact the Oregon

Historical Society at 503.306-5247)

|

|

1905

Lewis & Clark Exposition, the forestry building. The

strucure was 102 feet wide by 205 feet long, and its great

height was 70 feet. Construction of the building used two

miles of five and six foot logs, five miles of poles and

tons of shakes and cedar bark shingles. (courtesy of Oregon

Historical Society, #cn 62922, www.ohs.org)

Story

of the Chinook Salmon and His Foes on the Columbia

River

Lewis

and Clark Found King of Fresh Water Fishes a

Refreshing Change From Dog - How Salmon Are Caught

- The Fishermen Who Catch Them - How the Fish are

Packed - The Exhibit at the Lewis and Clark

Exposition.

By

W.E. Brindley

A

century ago two hardy adventurers, Captains

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who, in their

efforts to cross the country to the Pacific with a

band of 40 followers, had suffered untold

hardships, including the eating of dog, found a

most refreshing change of diet when they reached

the Columbia river. There for the first time they

saw the famous Chinook salmon, king of fresh water

fish, and tasted its luscious, rose pink flesh. To

the weary, half starved travelers the salmon seemed

a most welcome addition to a menu which had for

weeks consisted of crow, berries, an occasional

wolf or deer and the wolfish dogs which they bought

of the Indians. The captains recorded the incident

of the change of diet in their journals, and

Captain Clark made a rude sketch of the

fish.

|

Salmon

Exhibit at the Fair.

At

the Lewis and Clark exposition, which is to be held

at Portland, Ore., during this coming summer, from

June 1 to October 15, in commemoration of the

journey of Captains Meriwether Lewis and William

Clark, a most interesting exhibit will consist of a

complete exposition of the salmon industry,

together with specimens of live salmon in tanks,

and dead salmon in glass jars, of salmon eggs and

salmon fry and methods of salmon

hatching.

The

exhibit will show how the salmon are canned, and

how they are preserved by cold storage. It will be

one of the many interesting things about the

western world's fair, which, while a world's fair

in every sense, will aim particularly to show the

resources and progress of the Pacific Northwest, a

country which was added to the domain of the United

States as a direct result of the Lewis and Clark

expedition.

Spokesman-Review,

February 26, 1905, excerpted. Copyright 1905.

Reprinted with permission of The

Spokesman-Review.

|

|

|

200

Years Later

|

|

|

|

Explorers:

Nation's river system is 'sick'

During

4,000-mile journey from St. Louis to Portland, duo

find rivers worse than expected.

By

Jeff Barnard, of The Associated Press

PORTLAND,

Ore. -- Two men, who traced the western route of

Lewis and Clark said Thursday they found the

nation's river system in far worse shape than they

expected when they set out on the 4,000-mile

journey.

"We

came into this with our eyes open, but we did not

know the scope," Tom Warren said at a news

conference.

"The

rivers remind me of an epitaph on a tombstone,"

said John Hilton. "It said, 'I told you I was

sick.'"

The

men said they found rivers drowned by dams, dried

up by irrigation and fouled by agricultural and

industrial pollution.

"The

rivers remind me of an epitaph on a

tombstone. It said, 'I told you I was

sick.'"

|

After

the news conference, the men boarded a jetboat for

a six-hour trip to Astoria. There they got in

canoes and poled up the Lewis and Clark River to

Fort Clatsop National Memorial, a re-creation of

the place where the explorers spent the winter of

1805 before returning east.

"It's

one thing when you read the journals and another

when you feel it," Warren said. "We've gotten to

feel it."

Fort

Clatsop National Memorial superintendent Cynthia

Orlando presented Warren and Hilton with bronze

medals commemorating their trip and praised them

for bringing so much public attention to the state

of the environment.

A

fiddle player played "The Rose Tree," an 18th

century reel as Warren and Hilton beached their

fiberglass canoes on the muddy landing at Fort

Clatsop. In the bows of the canoes were two park

employees dressed in buckskins, coonskin caps and

red life jackets.

They

crossed 40 dams ascending the Missouri

River system and eight going down the

Snake and Columbia rivers. The first 800

miles of the Missouri River was a "muddy

ditch" filled with barges.

|

Warren,

39, is a chiropractor from Tulsa, Okla., and

Hilton, 47, is a college administrator from Flat

River, Mo.

They

set out from St. Louis on June 1 to follow the

journey Capt. Meriwether Lewis and Lt. William

Clark took 187 years ago. The expedition helped

open the West to commerce and

settlement.

Lewis

and Clark left St. Louis on May 14, 1804, with 45

men, a 55-foot keelboat and two large canoes to

trace the Missouri River to its headwaters for the

first time.

|

According

to the theories of the day, they expected to make

an easy half-day's hike across gentle ground to the

headwaters of the Columbia River, and follow that

to the Pacific.

President

Thomas Jefferson commissioned the expedition to

find a Northwest Passage that would wrest the fur

trade from the British and an alternative to the

perilous sailing around Cape Horn to

China.

It

took Lewis and Clark a year and a half to reach the

mouth of the Columbia. Warren and Hilton took three

months. Where Lewis and Clark poled, rowed, sailed

and towed their boats up the Missouri, Warren and

Hilton left behind their jetboat and poled canoes

100 miles up the Beaverhead River.

"It's

like climbing a mountain, on water," Warren

said.

They

rode horses and bicycles to trace the explorers'

350-mile route across the Bitterroot Mountains,

then got back into canoes to go down the Clearwater

River.

Arriving

at Lewiston, they returned to the jetboat to

descend the Snake River to the Columbia.

They

crossed 40 dams ascending the Missouri River system

and eight going down the Snake and Columbia rivers.

The first 800 miles of the Missouri River was a

"muddy ditch" filled with barges, Warren said. The

Beaverhead in Montana suffered from water

withdrawals for irrigation.

Where

Lewis and Clark saw timber on the banks of the

Columbia, Warren and Hilton stood in a meeting room

of a big hotel after stopping in

Portland.

The

decline of Pacific salmon on the Columbia

system from 30 million in Lewis and

Clark's time to 300,000 now illustrates

the crisis state of rivers

|

.

Ted

Strong, director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal

Fish Commission, welcomed Warren and Hilton on

behalf of native Americans, and said he hoped their

trip would help restore the health of rivers hurt

by development.

"When

Lewis and Clark guided their canoes and rafts on

the Columbia River they did not realize that while

on the surface they encountered Indian nations,

there were other nations that lived underneath the

water," he said. "Those nations are the nations of

aquatic life, primarily the salmon."

Kevin

Coyle, president of American Rivers, a conservation

group that helped sponsor the trip, presented

Warren and Hilton with medals.

He

said the decline of Pacific salmon on the Columbia

system from 30 million in Lewis and Clark's time to

300,000 now illustrates the crisis state of

rivers.

"The

rivers are sending us a message," he said. "They

are leading the decline."

|

|

|

River

of Kings

In

years past, the Spokane River was home to millions

of salmon, which brought bounty to the region's

tribes

Jim

Kershner, Staff writer, Spokesman

Review

Everybody

knows that salmon once surged through the Spokane

River.

But

not everyone knows that it was, literally, one of

the king rivers of the Northwest:

The

Spokane River spawned the biggest of the big

salmon, summer chinooks (kings) that were commonly

50 to 80 pounds.

The

Spokane River was one of the most productive salmon

streams in the entire Columbia system.

The

summer fishing camps at Spokane Falls were famous

among many tribes, even tribes from far away. The

total number of salmon running up the Spokane

probably approached a million annually, of which

about 300,000 were harvested by the Spokane tribe

and other tribes.

The

Spokane River spawned the biggest of the

big salmon, summer chinooks (kings) that

were commonly 50 to 80 pounds.

|

Spokane's

early hotels did a thriving business among Eastern

fishermen. The salmon were Spokane's first major

tourist attraction.

And

then they were gone.

After

hundreds of thousands of years of salmon runs, it

took less than a century to kill off the runs

entirely. Actually, it took less than two days -

the day that Long Lake Dam blocked the upper

three-quarters of the Spokane in 1915, and the day

that the Grand Coulee Dam blocked the Columbia and

the rest of the Spokane, in 1939. Both dams went up

without fish ladders.

Today,

it's hard to even visualize how alive the river

used to be with fish.

"Large

schools of salmon swam around in circles,

between [Spokane] falls and Bowl

and Pitcher. At the confluence of Latah

Creek, there were shoals of salmon that

just sat there." -- fisheries

biologist Dr. Allan Scholz

|

In

1839, The Rev. Elkanah Walker, a missionary, wrote

the following about a Spokane Indians fishing camp

at Little Falls on the Spokane: "It is not uncommon

for them to take 1,000 in a day. It is an

interesting sight to see the salmon pass a rapid.

The number was so great that there were hundreds

constantly out of the water."

The

famous British botanist David Douglas wrote this in

1826: "The natives constructed a barrier across the

Little Spokane (where it enters the Spokane). ...

After the traps filled with salmon, the Indians

would spear them. 1,700 salmon were taken this day,

now two o'clock; how many more may still be in the

snare, I do not know."

And

these two fishing camps, at Little Falls and at the

mouth of the Little Spokane, weren't even the

biggest of the three main fishing sites on the

Spokane River. The premier camp was the big one

just below the Spokane Falls, smack in the middle

of what is now the city of Spokane.

Few,

if any, salmon could get above the falls; most of

these enormous "hogs" spawned right

there.

"Large

schools of salmon swam around in circles, between

the falls and Bowl and Pitcher," said Dr. Allan

Scholz, a fisheries biology professor at Eastern

Washington University. "At the confluence of Latah

Creek, there were shoals of salmon that just sat

there."

It

was as important as any fishing site on the

Columbia itself, including the famous fishing spots

at Celilo Falls near The Dalles and Kettle Falls,

according to Scholz.

Debbie

Finley, a historian, member of the Colville

Confederated Tribes and granddaughter of a Spokane

Indian elder, said that anywhere between 200 and

5,000 Indians gathered on the Spokane every year,

some of them coming from hundreds of miles

away.

|

THE

FOUR LOWER SNAKE RIVER DAMS.

When Lewis & Clark first stepped foot into the

Columbia River watershed, this was the richest

salmon fishery on earth. Sixteen million wild

salmon yearly pulsed these wild forests and

deserts, returning home to natal streams, spawning,

and in their death renewing a cycle of life.

Where Lewis & Clark canoed free-flowing waters

on the Snake River, today the river has been

stilled by four federal dams. These four lower

Snake River dams form a channel of death for the

young salmon.

The wild salmon that saved Lewis & Clark now

face extinction. Decisions made by the United

States during the Bicentennial will determine the

fate of Columbia River salmon. [Army Corps of

Engineers photos]

Lower

Granite Dam

Little

Goose Dam

Lower

Monumental Dam

Ice

Harbor Dam

|

|

"My

original people are from the Arrow Lakes in Canada,

and we came down in birch-bark canoes, for

thousands and thousands of years," said

Finley.

In

fact, when Lewis and Clark came down the Clearwater

in 1805, they wondered where all the Nez Perce

were. They were told: They're up on the Spokane

River, fishing.

A

salmon chief from the resident Spokane tribe would

oversee the fishing and then oversee the

distribution of the catch equally among all the

diverse bands.

"Every

single person received equally, no matter their

age," said Finley.

The

Spokane aquifer deserves the credit for

this. Cool underground water gushes into

the Spokane River at a number of spots,

keeping the stream cool in the summer and

unfrozen in the winter.

|

According

to Scholz, the Spokane Indians depended more

heavily on salmon for sustenance than almost any

other tribe in the entire Columbia system. An

Indian agent in 1866 estimated that salmon made up

five-eighths of their total diet.

Thousands

of enormous chinooks would be spread out to be

sun-dried, wind-dried or smoked. The preserved fish

lasted through the winter and were traded to other

tribes for buffalo hides, shells and

obsidian.

And

when the fishing was done, the games would begin.

On the plain where West Riverside Avenue stretches

today, the Indians established a horse-racing

course.

The

salmon camps persisted even after the city of

Spokane Falls was established in 1881. The salmon

camps lasted until the salmon no longer came in

1915.

When

Lewis and Clark came down the Clearwater

in 1805, they wondered where all the Nez

Perce were. They were told: They're up on

the Spokane River, fishing.

|

The

white settlers, too, took advantage of the river's

richness. Around the turn of the century, The

Spokesman-Review was full of stories of

50-pounders being taken by fishermen.

"At

one time, Spokane was internationally known for its

fishing," said Scholz, upon whose research most of

this article is based. "Some of the big hotels were

built in part to bring people here for these kind

of fishing experiences."

Not

only was the river famous for its chinook salmon

run, but it also had two steelhead runs, a small

coho run, and, above the falls, a huge population

of cutthroat trout.

After

hundreds of thousands of years of salmon

runs, it took less than a century to kill

off the runs entirely. Actually, it took

less than two days.

|

When

Lt. N. Abercrombie of the U.S. Army went fishing on

Havermale Island (Riverfront Park) in 1877, he

wrote: "Caught 400 (cutthroat) trout, weighing two

to five pounds apiece. As fast as we dropped in a

hook baited with a grasshopper, we would catch a

big trout. In fact, the greatest part of the work

was catching the grasshopper."

There's

a sound biological explanation for all of this

abundance. The Spokane River just plain had more

fish-food than most streams, mainly

insects.

"The

invertebrate numbers are astoundingly high, even

now," said Scholz.

The

Spokane aquifer deserves the credit for this. Cool

underground water gushes into the Spokane River at

a number of spots, keeping the stream cool in the

summer and unfrozen in the winter. These are ideal

conditions for developing a "really large

invertebrate population," said Scholz.

Even

with those advantages, the Spokane salmon could not

survive what happened between about 1870 and 1939.

The first blow came with the development of

commercial salmon canneries on the lower Columbia.

Those canneries went after the biggest chinooks,

which happened to be the Spokane River strain. By

the late 1880s, the Spokane runs had noticeably

shrunk, said Scholz.

|

Then

came two much more serious blows. Little Falls Dam,

right near one of the main salmon camps, was

completed in 1911. It had only a rudimentary fish

ladder; there was some dispute over whether fish

could negotiate it at all.

"From

the standpoint of the environment, I'm

just aghast."

--

Dr. Allan Scholz, fisheries

biologist

|

By

1915, it was a moot point. Long Lake Dam was built

that year, four miles above Little Falls Dam,

without any fish ladder at all.

"It

was a sad day for the pioneers who had grown to

depend on the salmon as one of their staple foods,"

wrote D.L. McDonald, a settler on the Spokane

River, quoted in "The Spokane River: Its Miles and

Its History" by John Fahey and Bob Dellwo. "But for

the Indians, it was a catastrophe."

Salmon

were restricted to the lower 28 miles of the river

below Little Falls. Then in 1939, the Grand Coulee

Dam blocked off the Columbia, which sealed the

salmon off from the entire Spokane

River.

"Of

those really large strains that came into this

area, it's unlikely that there are any (genetic)

remnants left," said Scholz.

"River,

do you remember how it used to be - the

game, the fish, the pure water, the roar

of the falls, boats, canoes, fishing

platforms? You fed and took care of our

people then. For thousands of years we

walked your banks and used your waters.

You would always answer when our chiefs

called to you with their prayer to the

river spirit. Sometimes I stand and shout,

'RIVER, DO YOU REMEMBER US?'"

--

Chief Alex Sherwood, Spokane Indian

Nation

|

Today

the Spokane River is mostly a slow-water river.

Instead of salmon, it contains carp, bass,

bluegills, northern pike, yellow perch and "lots of

suckers," said Scholz.

The

free-flowing sections - from Riverfront State Park

upstream to Post Falls - still contain good

populations of trout, feeding on those prolific

insects.

But

those 50-plus pound chinooks are visible only to

those who use their imagination.

"I'm

a little wistful that I wasn't here to see it,"

said Scholz. "And from the standpoint of the

environment, I'm just aghast. We've gone from a

river system that was very productive to one that

is totally regulated. But the biggest thing is the

loss of the Indian culture."

It's

an ache that remains acute. In 1972, Chief Alex

Sherwood of the Spokane tribe stood on a restaurant

deck, looking out over the falls, and looked back

in time. In "The Spokane River: Its Miles and Its

History," co-author Bob Dellwo quoted the chief's

words that day:

"Sometimes

even now I find a lonely spot where the river still

runs wild. I find myself talking to it. I might

ask, 'River, do you remember how it used to be -

the game, the fish, the pure water, the roar of the

falls, boats, canoes, fishing platforms? You fed

and took care of our people then. For thousands of

years we walked your banks and used your waters.

You would always answer when our chiefs called to

you with their prayer to the river spirit.'

Sometimes I stand and shout,

'RIVER,

DO YOU REMEMBER US?'"

The

Spokesman-Review, August 21, 1995, Copyright

1995. Reprinted with permission of The

Spokesman-Review.

|

|

|

"Capt.

Clark" at the National Press Club, March

2000

My

name is Captain William Clark. Along with my dear

friend here, Captain Meriwether Lewis, I led an

expedition that every school child in America

knows.

I

have come today to remind you of our 8,000-mile

journey and of the salmon and Indians who saved our

lives.

Ours

was the Corps of Discovery. We carried the hopes of

our country scarcely 30 years old. Our journey

crossed the continent from the doorstep of

Monticello, home of President Thomas Jefferson,

through St. Louis, to the mouth of the Columbia

River.

We

rendezvoused in St. Louis on the Mississippi and

launched our boats up the Missouri. After nearly 15

months of toilsome days and restless nights, we

found the furthermost fountain of the Missouri

River.

We

now stood on a continental divide between two great

rivers: the Missouri flowing east, and a new river

flowing west. We drank of this cold clean water.

This was the water of the Snake River, tributary to

the mighty Columbia River.

The

trail left the rivers and grew treacherous. So

steep were the mountains that any man or horse that

fell would be dashed to pieces. September snow

fell. We were cold, starving, and exhausted. Our

expedition and our nation's hopes teetered on the

brink of disaster.

I

left Captain Lewis and the party and went forward

in search of food. It was then that I encountered

the Nimipoo (Nee-me-poo), the Nez Perce. At this

most vulnerable moment they could have ended our

lives. The Nez Perce welcomed us. They fed us

salmon and camus root.

The

Indians and salmon saved the Lewis & Clark

expedition. Our survival meant the United States,

not the British, would claim most of the mighty

Columbia River.

I

have come here today to remind you of all this. For

you as a nation are deciding the fate of the salmon

that saved the Corps of Discovery.

In

these waters we saw salmon so thick you could not

dip an oar without striking a silvery back. No

longer. These free flowing waters we canoed on the

Snake River have been stilled by four dams. These

four lower Snake River dams are killing the salmon

and form a channel of death.

As

you prepare for the Lewis & Clark Bicentennial,

the monument you must build is simple: to restore

the lower Snake River as a free-flowing river.

Remove the dams. Save the salmon.

We

have a moral duty and legal obligation to do

this.

Do

not shame Capt. Lewis and me with this great

injustice of allowing the salmon to go extinct.

Honor your treaties promising the salmon will

endure.

Celebrate

the Lewis & Clark Bicentennial by saving the

salmon. We were the Corps of Discovery. Capt. Lewis

and I challenge you as a nation to be a Corps of

Recovery.

"Capt. William Clark" speaking at the National

Press Club, March 9, 2000, on the occasion of the

recognition of the Snake River as the nation's most

endangered river by American Rivers.

|

"Capt.

Clark" at the DeVoto Grove of Ancient Cedars,

Clearwater National Forest, Sept. 2000. Photo:

Chase Davis

".

. . The Nez Perce Tribe welcomed us. They

fed us salmon and camas root.

The

Indians and salmon saved the Lewis &

Clark expedition. Our survival meant the

United States, not the British, would

claim most of the mighty Columbia

River.

I

have come here today to remind you of all

this. For you as a nation are deciding the

fate of the salmon that saved the Corps of

Discovery.

In

these waters we saw salmon so thick you

could not dip an oar without striking a

silvery back. No longer. These free

flowing waters we canoed on the Snake

River have been stilled by four dams.

These four lower Snake River dams are

killing the salmon and form a channel of

death.

As

you prepare for the Lewis & Clark

Bicentennial, the monument you must build

is simple: to restore the lower Snake

River as a free-flowing river. Remove the

dams. Save the salmon.

We

have a moral duty and legal obligation to

do this.

Do

not shame Capt. Lewis and me with this

great injustice of allowing the salmon to

go extinct. Honor your treaties promising

the salmon will endure.

Celebrate

the Lewis & Clark Bicentennial by

saving the salmon. We were the Corps of

Discovery. Capt. Lewis and I challenge you

as a nation to be a Corps of

Recovery."

|

|

|

Mt.

Rainier, clearcuts. Failure of the Lewis and Clark

Expedition to find a water route to the Pacific Ocean would

eventualy lead to building the transcontinental railroads.

Encouraged by land grants awarded to railroads in the 1860s,

timber companies started clear-cutting the Northwest in the

late 1800s. © Trygve Steen

|

|

Explorers

Opened Timber Chapter

Shots

Signaling 1804 Trip Echo In Panel's

Action

By

William Allen, Post-Dispatch Science

Writer

THE

BATTLE OVER America's rain forest is the climax of

a chapter in American history that started in the

St. Louis area 188 years ago Thursday.

On

May 14, 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

embarked from a camp near St. Louis with orders

from President Thomas Jefferson to explore the

territory west of the Mississippi River. They

marked the occasion by firing a shot.

The

events they set in motion prompted new shots in

Washington Thursday - exactly 188 years later - in

an ongoing environmental battle. The latest

skirmish in the battle involved a decision by

President George Bush's administration to remove

protections for the threatened northern spotted

owl.

Lewis

and Clark described the towering

old-growth forests they found in the

Pacific Northwest.

|

In

reports to Washington, Lewis and Clark described

the towering old-growth forests they found in the

Pacific Northwest.

Encouraged

by land grants awarded to railroads in the 1860s,

timber companies started clear-cutting the

Northwest in the late 1800s.

Over

the next few decades, Congress and various

presidents preserved some forest land by

designating national parks and wilderness areas.

Timber companies could still cut on vast stretches

of public land, including national forests and

property managed by the federal Bureau of Land

Management.

The

Timber Basket

About

20 million acres of old-growth forest once stood in

Oregon and Washington, forestry experts estimate.

Just 2.3 million acres are left, most of it on

public land. About 900,000 acres are protected in

national parks or wilderness areas.

The

1.4 million acres of old growth that are left are

subject to logging, primarily on federal lands like

national forests and holdings managed by the

federal Bureau of Land Management.

''This

was the nation's timber basket and we cut like

there was no tomorrow,'' said Bill Arthur, of the

Sierra Club in Seattle. ''Now we're at the end of

the timber frontier.''

The

U.S. Forest Service has been criticized strongly

for allowing timber companies to profit from

cutting vast tracts of national forest while

taxpayers pay for expensive logging roads. Much of

that criticism has come from within the agency's

own ranks.

The

Battle Ensues

When

the pace of cutting accelerated in the 1980s,

environmentalists moved to block what they saw as

the final destruction of the Northwestern

forests.

Their

weapon: the northern spotted owl.

The

owl relies on broad areas of old-growth forest for

survival, and scientific studies were showing a

dramatic decline in owl populations.

In

1987, the environmental groups petitioned the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service to list the owl as an

endangered species under the Endangered Species

Act. Such a listing would require the agency to

develop a ''recovery plan'' for the owl and set up

measures to protect ''critical

habitat.''

The

environmental groups initiated court action that

continues today. Judges barred timber sales on many

tracts of federal land.

After

rejecting the owl listing in 1987, the Fish and

Wildlife Service finally proclaimed the owl

threatened three years later. Last year, the agency

proposed setting aside 11.6 million acres of forest

to protect the owl but reduced the figure by half a

few months later.

Environmentalists

charged that Bush's administration had bowed to

pressure from the powerful timber industry

lobby.

Enter

a Cabinet-level committee dubbed by

environmentalists ''the God Squad.''

In

January, Bush's administration initiated hearings

in Portland before an administrative law judge to

assess the need to protect the owl.

Based

in part on expert testimony at the hearing, the

committee voted 5-2 Thursday to override the

Endangered Species Act and allow logging on 1,700

acres of Oregon forest that is part of the owl's

habitat. The act allows such exceptions to be made.

The land on which logging will resume is managed by

the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

The

panel earned its nickname because of its power to

let a species go extinct. Among the panel's members

is Agriculture Secretary Edward Madigan, a former

congressman from central Illinois. He voted to

allow logging to resume.

The

timber industry and loggers have used the owl to

turn the tables on the environmentalists, casting

the owl as the needless cause of job loss. The

industry also has trained its sights on the

Endangered Species Act.

|

Industry

officials deny that the owl is becoming extinct and

warn that the nation faces an ''endangered species

gridlock'' that will tie up economic

progress.

"The

environmentalists have been very good in portraying

the idea that the last tree is going to get cut,''

said Chris West, of the Northwest Forestry

Association, an industry group in Portland." If we

continue to lock up land, we're going to shut more

mills, lose more jobs and run out of forest

products,'' West said.

Countered

the Sierra Club's Arthur: ''The change is going to

happen. The issue is, are you going to make some

conscious decision now or simply going to cut

through to the end?''

A

spotted owl carcass or two showed up nailed to a

tree. Loggers talked of selling canned owl meat to

the ''tree-huggers.''

And

some environmentalists charged that when a logger

looked at a 500-year-old Douglas fir, all he could

see was a bunch of two-by-fours waiting to be

liberated.

Enter

The Scientists

Before

the God Squad was even convened, President Ronald

Reagan's administration had asked a panel of

experts from several federal agencies to develop a

scientifically credible plan to help the owl avoid

extinction. Heading the panel was Jack Ward Thomas,

a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Forest Service

in Oregon.

In

April 1990, the Thomas committee submitted a plan

to Congress to set aside large ''habitat

conservation areas'' on land managed by the Forest

Service and Bureau of Land Management over a

broader portion of the Pacific Northwest. The

plan's adoption would result in the owl population

dropping by half, the panel said.

"This

was the nation's timber basket and we cut

like there was no tomorrow. Now we're at

the end of the timber frontier."

|

The

scientists emphasized that the entire forest

ecosystem - not just the owl - was at

stake.

Industry

complained that the plan would take too much land

from logging. Environmentalists complained that it

would take too little.

Rep.

Harold Volkmer, D-Hannibal, ordered another study.

Volkmer heads a pivotal House subcommittee on farms

and forests.

A

group of leading forestry scientists known as the

''Gang of Four'' convened. The panel included

Thomas, Jerry Franklin of the University of

Washington, K. Norman Johnson of Oregon State

University and John Gordon of Yale University. The

Portland press corps gave the group its name

because of its independence from any

agency.

The

Gang of Four, with help from several specialists,

gathered all available scientific data and listed

options that balanced timber harvest levels against

protection of owls and endangered fish. They made

no single recommendation.

''The

Thomas report injected scientific credibility into

the debate,'' Johnson said. ''The Gang of Four

report analyzes the data and passes the choices to

Congress of the acceptable level of risk'' for the

owl and other species.

Said

Volkmer: ''We have used that scientific basis for

the first time in writing legislation that affects

our national forests. In doing so, we looked at the

ecology of the national forest. That's quite a

difference from the way we've approached this in

the past.''

On

a 7-6 vote last week, Volkmer's subcommittee sent

to the full Agriculture Committee a bill that used

the report as a basis to balance timber production

with protection of owls, salmon and other

animals.

Volkmer's

bill as well as one now moving through the House

Interior Committee could form the basis for a new

law that would pre-empt many of the logging

decisions made by the administration and the

courts.

Volkmer

has won praise from scientists and

environmentalists for bringing a scientific

foundation to Northwestern forest

legislation.

As

the Gang of Four noted in its report: ''Science has

done what it can. The process of democracy must go

forward from here.''

How

America's rain forest will be managed is now in the

hands of Congress.

St.

Louis Post-Dispatch, May 15, 1992. Reprinted

with permission of the St. Louis

Post-Dispatch, copyright 2002.

(http://home.post-dispatch.com).

|

|

|

Clearcut

controversy

Forest

Service questions timing of Plum Creek's pine

forest harvest along Lewis and Clark

Trail

By

Sherry Devlin of the Missoulian

LOLO

PASS - Knowing that the U.S. Forest Service wanted

to buy the land and protect its historic value,

Plum Creek Timber Co. clearcut a lodgepole pine

forest sheltering the Lewis and Clark Trail near

Lolo Pass.

Then,

with the bicentennial of the historic expedition

approaching and amid predictions that millions of

tourists would follow the explorers' route, Plum

Creek said "no" to the Forest Service's purchase

offer and instead sold the government an easement

allowing public access to the trail.

Alternately

called the Lolo Trail, the Nez Perce Trail

and the Lewis and Clark Trail, the

120-mile route from Lolo, Mont., to

Weippe, Idaho, is a priceless historic

artifact.

|

Now

some say the logging stripped the land of its

historic setting at the very moment the national

spotlight was set to shine on the trail that gave

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark passage through

the Bitterroot Mountains in 1805 and 1806 - as it

had the Nez Perce and Salish Indians for centuries

before.

"It

is almost inconceivable that Plum Creek could have

undertaken this project knowing the bicentennial

was ahead," said Gene Thompson, a forestry

technician who oversees trail maintenance for the

Lolo National Forest. "That's what saddens me. This

is the first time the trail has had so much

attention focused on it.

"By

all indications, a lot of people will come over

this trail in the next few years. I just wish they

could have seen this section as it appeared 18

months ago. This was a place where you could really

understand the trials of the Native Americans and

the trials of Lewis and Clark when they encountered

these mountains."

"The

historic tread remains, but the integrity of the

setting has been lost," said Lolo National Forest

archaeologist Milo McLeod. "It is unfortunate that

Plum Creek could not have been more sensitive to

the value of the historic setting."

In

September of 1805, the Lewis and Clark

expedition nearly met its end on the Lolo

Trail, so scarce was the game and so early

the snowfall. And in the summer of 1877,

750 Nez Perce Indians tried to escape

pursuing soldiers by crossing the trail

into Montana.

|

An

adjoining, uncut section of national forest land

provides the picture of what Plum Creek's land

looked like 18 months ago, when a crew of Nez Perce

and Salish teen-agers cleared the Lolo Trail from

Lee Creek campground to Packer Meadows, then rode

the trail on horseback.

There

was no break in tree cover from the national forest

to the industrial forest in July 1999. For 2.5

miles, the trail ran through an intact forest,

uncut by public or private foresters, left to grow

for the 90 years since the Bitterroot Mountains

burned in the fires of 1910.

It

was, Thompson said, the largest piece of intact

forest on the Lolo Trail in Montana.

Now

the edge of the national forest is marked by a line

of 90-year-old lodgepole pines, their sides painted

red to show the change in ownership. Cross into the

national forest and the scene is dark, cool and

green. Turn around and traverse the adjoining Plum

Creek section and the mountainside is open; a

handful of spindly lodgepoles remains; the growth

is at ground level, where foresters have planted a

new forest.

Few

Forest Service or Plum Creek employees have seen

the Lee Creek clearcut. In fact, the Plum Creek

land-use manager who lauded the easement during a

ceremony in Packer Meadows last month conceded

Friday that he has not seen the site.

"My

company and our predecessors have managed this area

for many decades as part of our working forest,"

Jerry Sorensen said at the July 25 celebration.

"And for as long a time, we have recognized the

special importance of this area and have protected

the integrity and the character of the Lolo

Trail."

On

Friday, Sorensen said the federal government

"bought an easement, not the land" in Lee Creek.

Plum Creek never hid the fact that the timber would

be actively managed, he said.

"Our

foresters felt this was the best way to manage that

ground for the long term, not just for the two

years of the Lewis and Clark celebration," said

Plum Creek spokeswoman Kris Russell. "We are

looking at the forest over decades, not over a

couple of years."

The

open hillside below Wagon Mountain has not lost its

forest, Russell insisted. "This is a forest. It is

just a very, very young forest. A lot of people

would refer to the forest next door as a biological

desert, or darn close to it. But now you're getting

into a huge philosophical discussion. Is a forest

something that has trees on it or is a forest a

place where trees are growing?"

"It

is almost inconceivable that Plum Creek

could have undertaken this project knowing

the bicentennial was ahead."

|

"I

don't think a doghair lodgepole stand is a whole

lot better looking than a clearcut," she

said.

Lolo

National Forest supervisor Debbie Austin said she

was not surprised when her staff reported that the

land had been logged during the two years she was

negotiating the easement with Plum Creek. "There

were some expectations that some people had, and

those people were quite surprised when this

happened," she said. "I was not."

"Plum

Creek agreed to sell portions of land containing

the Lolo Trail, but they were not willing to sell

Section 1," Austin said. "They were willing to give

us public access by way of an easement, and that

was what we purchased. I always knew the management

would be different in Section 1. All we acquired

was a 15-foot trail easement."

During

negotiations, Austin said she asked Plum Creek

foresters if they could take a "lighter touch" in

managing the forest alongside the historic trail.

"But they told me they would be managing this land,

that they wanted to manage the trees. At that point

in the negotiations, my choice was to protect the

trail tread and public access, or to walk

away.

"I

felt the trail was more important than walking

away."

"This

is the way I chose to look at it," Austin said. "It

was really important to protect the trail and to

provide access for the public in perpetuity. That

was the most important thing. It was private land,

and we couldn't go in and take somebody's private

land away from them."

The

Forest Service paid $4,600 for trail easements on

two sections of Plum Creek land, one of which was

the recently clearcut Section 1.

Russell

said her company does not sell timberland "that we

think we can manage well for long-term forestry."

Section 1 was good, productive timberland, she

said.

"The

Forest Service knows that giving them an easement

doesn't mean we will stop managing the forest the

way we think we should manage a forest," Russell

said. "We are not the kind of company that hides

its work. We think we do a good job of managing the

forest and don't try to hide that by not doing

it."

A

clearcut was the right forestry prescription for

the lodgepole stand in Lee Creek, Russell said. "We

did what was right for the ground. I do not feel it

diminishes the trail or its importance or the

easement or its importance. The easement is in

perpetuity, as is the forest."

|

"The

reason it was clearcut was because it was lodgepole

pine," she said. "There is not a whole heck of a

lot else that you can do with that sort of stand.

If you do a selective harvest, all the trees you

left are going to fall down. If you are ever going

to do anything with it, you have to clearcut

it."

"This

was a place where you could really

understand the trials of the Native

Americans and the trials of Lewis and

Clark when they encountered these

mountains."

--

Gene Thompson, Lolo National

Forest

|

Lodgepole

forests like those atop Lolo Pass "grew up out of a

fire ecology where they burned to the ground,"

Russell said. A clearcut is how a forester mimics

nature's stand-replacing fires.

"In

lodgepole, you don't have a forestry option," she

said. "It wouldn't do any good to leave a buffer

along the trail. All the trees would blow over. The

same would be true if we left a few more trees per

acre. From our foresters' perspective, they are

trying to grow a forest."

Plum

Creek abided by all good-forestry precepts and

best-management practices in logging the historic

trail, Russell said. The riparian area at the base

of the hillside was not logged. There, the Lolo

Trail runs through a lush forest and hops a little

creek.

Forest

Service officials did not disagree with Russell's

assessment. "This is private land," Thompson said.

"What was done here was within the legal rights and

responsibilities of the landowner. This landscape

abides by best management practices for forestry in

the state of Montana."

The

public-access easement puts no restrictions on Plum

Creek's management of the land. If logging disrupts

access, the company must provide an alternate

route. If the trail is damaged by the company's

management, it must be restored.

But

for Thompson, who - with archaeologist McLeod -

visited the site last week at the Missoulian's

request, the question is not one of laws broken or

responsibilities shirked, but one of timing. For

McLeod, it is one of preserving the integrity of a

trail that has national significance.

"Knowing

that this was the Lolo Trail, they could have been

more sensitive," McLeod said. "They could have left

a corridor."

Thompson

and McLeod had hoped the Forest Service would be

able to buy Section 1, as it did another 1,248

acres owned by Plum Creek on steeper, less

profitable ground nearby. In the same transaction

that provided the easement across the Lee Creek

clearcut, the federal government paid $1.6 million

for other sections of Plum Creek land through which

the historic trail passes.

That

now-public acreage will be managed so visitors see

no signs of modern management, Austin said. But

Plum Creek will determine how the private

timberland is managed.

The

Lolo Creek drainage has been logged since the

1920s, first by industrial foresters, then by the

Forest Service, McLeod said. Much of the timberland

is in a checkboard ownership pattern - one section

of Plum Creek, one section of national forest, one

more section of Plum Creek.

"The

intermix of management has always been a

challenge," McLeod said, "particularly since the

Lolo Trail was named a National Historic Landmark,

and then was placed on the National Historic

Register. This is a place significant to our

nation's history, but it is also an industrial

forest."

McLeod

wrote his master's thesis on the Lolo Trail and

pinpointed its location over the past two decades.

Alternately called the Lolo Trail, the Nez Perce

Trail and the Lewis and Clark Trail, the 120-mile

route from Lolo, Mont., to Weippe, Idaho, is a

priceless historic artifact, he said.

And

while Russell said Plum Creek foresters were not

certain of the trail's location, McLeod said there

is no doubt - and has not been any doubt for

several years. He flagged the trail three years

ago, before the forest was logged. Thompson came

along with another set of markers two years ago;

he, too, was there before Plum Creek logged the

land.

"We

know this trail and its history and its use and its

significance," McLeod said.

For

hundreds of years, maybe longer, Salish Indians

traveled west over the trail to dig camas roots at

Lolo Pass and to fish for salmon and steelhead on

the Clearwater and Snake rivers. From the plateaus

of central Idaho came the Nez Perce people, headed

east onto the plains to hunt buffalo.

In

September of 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition

nearly met its end on the Lolo Trail, so scarce was

the game and so early the snowfall. And in the

summer of 1877, 750 Nez Perce Indians tried to

escape pursuing soldiers by crossing the trail into

Montana. They were sick, hungry and frightened;

most died in the flight, or at the Big Hole or

Bears Paw battlefields.

McLeod

said the Nez Perce's final crossing left the path

so deeply worn that he could find the tread more

than 100 years later. The trail and the land it

crosses are not pristine, he said. They have been

used by humans for centuries.

But

the Forest Service has protected the path and its

immediate surroundings in recent decades, deferring

to the land's historic value, McLeod

said.

Russell,

however, pointed to other places where her company

did no logging and eventually sold the land to the

public, including the Glade Creek campsite on the

Idaho side of Lolo Pass. "There are special places

like Glade Creek," she said, "where we approached

our management completely differently."

And

Plum Creek is negotiating the possible sale of (or

easements on) other tracts through which the Lolo

Trail passes in Idaho, some of the wildest

remaining country through which the Lewis and Clark

expedition passed.

Sometimes,

commercial timberland is logged before it is sold

to reduce the asking price, said Sorensen, the

company's land-use manager. Sometimes, it is logged

before an easement is granted because the work will

be more difficult afterwards.

Could

the Forest Service insist that the land not be

touched during the course of negotiations? "Yes,"

said Austin, the Lolo forest supervisor. But that

kind of demand could be a deal-breaker.

"It

depends on the values and the reasons why we want

to acquire a piece of property," Austin said. "If

those values are related to having a bunch of trees

on the land, then we need to say we want the trees

- and we have to pay for them."

In

the case of the land in Lee Creek, Austin said, "I

didn't feel the value was the trees. I felt the

value to the public was the access. Besides, access

was the only choice we were given."

The

Forest Service talked about Lolo Trail easements

for more than 10 years with both Plum Creek and

Champion International Corp. - before Champion sold

its Montana timberland to Plum Creek, Austin said.

Only in the past two years, after she became forest

supervisor and money was available to buy some

land, did the negotiations get serious.

"It

was a long, long negotiation to get to the point

where Plum Creek agreed to sell us anything," she

said. "On the last two sections - Sections 1 and 25

- they said, 'We cannot go any further, but we will

sell you an easement.'"

"It's

a fact," said Thompson, the forestry technician.

"It's their land and their timetable. Ultimately,

it has to come down to expectations, and mine were

maybe less realistic than others."

Reporter

Sherry Devlin can be reached at 523-5268 or at

sdevlin@missoulian.com.

Missoulian,

August 19, 2001,

Reprinted with permission of the

Missoulian.

|

|

Plum

Creek clearcutting near Lolo Pass, 1989. Photo: © John

Osborn

|

Clearcuts,

logging roads, and landslides, Clearwater National Forest.

Photo: © Bill Haskins

Clearwater

National Forest: A National Treasure in

Peril

When

Lewis & Clark explored the west, they did not

find a single clearcut or logging road. In the last

200 years the forests of the Northern Rockies,

Cascades, and coastal ranges have been heavily

clearcut, and bulldozed with hundreds of thousands

of miles of logging roads.

Today,

between Monticello and Astoria, the last remaining

wilderness section of the trail is in Idaho: the

Clearwater National Forest. Here it is possible to

walk in the footsteps of the Corps of Discovery,

and see the sweep of a wilderness landscape

unmarred by logging roads and clearcuts.

With

16 inventoried roadless areas totaling close to one

million acres, northern Idaho's Clearwater National

Forest retains much of the same wild character as

when Lewis & Clark first traversed the area 200

years ago. The Clearwater's many low-elevation

roadless areas and old growth forests are a rarity

even in America's National Forest

System.

|

Smoking

Cairn, Clearwater National Forest. Between

Monticello and Fort Clatsop there are few places

that are as wild today as they were at the time of

Lewis & Clark. Here at Smoking Cairn, the view

in nearly all directions is of wild country:

neither clearcuts nor logging roads.

Photo: © Chase

Davis

|

|

The

Clearwater is home to many pristine rivers and

streams. As its name implies, this national forest

is world-renowned for blue ribbon fisheries,

kayaking, and rafting. Sections of the Lochsa and

North Fork rivers remain wild drainages,

contributing to exceptional water quality. Because

of the forest's thin fragile soils, logging and

roadbuilding have threatened several rivers,

including the Palouse and Potlatch.

The

Clearwater's rivers and streams provide important

spawning habitat for westslope cutthroat, bull

trout, steelhead, and chinook salmon. All four have

either been listed as threatened, endangered or are

being petitioned for listing. Past logging and road

construction have caused landslides which decimated

fish populations in some drainages.

|

The

Clearwater's wildlands provide important habitat

for gray wolf, bald eagle, lynx, and possibly

grizzly bear. Recovery plans for grizzlies in the

Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness have been

proposed

Logging

and roadbuilding have impaired water quality and

fisheries on more than a third of this national

forest.

On

the eve of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial, the

U.S. Forest Service plans to log thousands of acres

of the Clearwater National Forest, further

despoiling this national treasure. Tourists

exploring the lands of Lewis & Clark will be

joined by logging trucks driving the winding, river

canyon Highway 12.

|

FOR

MORE INFORMATION,

CONTACT:

- FRIENDS

OF THE CLEARWATER

- www.wildrockies.org/foc

- 208.882-9755

- PO

Box 9241

- Moscow,

ID 83843

|

|

Next

Section

Return

To Lewis & Clark Home Page

|